Dementia is the second leading cause of death in Australia. Without a significant medical breakthrough, this is expected to increase to almost 900,000 by 2050, according to Alzheimer’s Australia. Older age is one of the strongest risk factors for dementia, and the risk is reported to double every five years after 65. Two-thirds of those suffering from dementia are women, and a recent review of studies on dementia shows women with Alzheimer’s have poorer cognitive abilities than men at the same stage of the disease.

Scientists once believed brain ageing was unavoidable because it was a direct consequence of neural machinery wearing down over time. However, over the past few decades, research has found an adult’s brain is still able to form new, memory-building neural networks in a process known as neuroplasticity. In other words, the aged brain remains capable in its ability to adapt to and benefit from new experiences. Encouragingly, there is now a body of research to suggest that a range of modifiable lifestyle and health factors have the potential to reduce the risk and delay onset of cognitive decline and dementia.

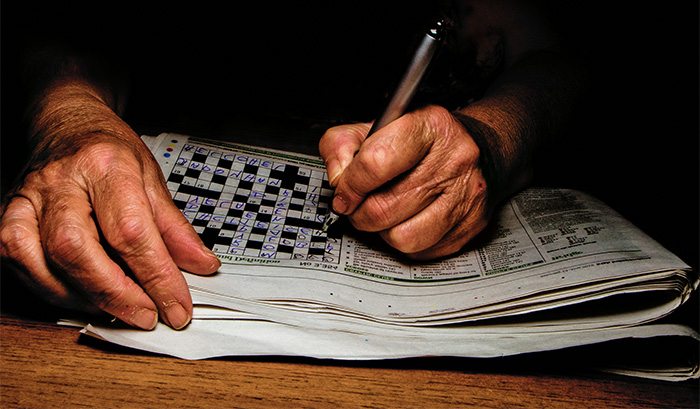

Try our puzzles to exercise your brain daily and see if you can crack the code.

Despite the evidence, there is a common misconception that cognitive decline and dementia are an inevitable result of ageing and that can be done to halt them. Alzheimer’s Australia reports that 40 per cent of Australians still do not understand that there actions that can be taken to reduce the risk of dementia. “There is no guaranteed prevention for dementia, but what many people don’t realise is there are things that you can do to boost your brain health and reduce your risk,” says Maree McCabe, acting CEO Alzheimer’s Australia. “There are things we can all do, and start doing now, to encourage healthy brain ageing.”

Physical activity to exercise your memory

“There is mounting evidence that regular exercise is crucial to preserving brain function with increasing age,” says Professor Cathie Sherrington, from The George Institute of Global Health. “For example, a recent study published in the scientific journal Neurology (with 1228 participants and a five-year follow-up period) found greater declines in cognitive abilities in those who undertook no or low levels of leisure time physical activity, after adjusting for other risk factors.”

In a landmark Australian study published earlier this year led by Dr Cassandra Szoeke, a consultant neurologist and associate professor of medicine at The Royal Melbourne Hospital and The University of Melbourne, daily physical activity was found to be the most important factor to impact on memory, in a group of 387 women, over a 20-year period. The key is to start exercising as soon as possible. “We found the strongest effect was cumulative,” says Dr Szoeke. “What people did every year mattered most. What women did in their 60s was as important as what they did in their late 40s. We saw women were able to ‘make up for lost time’ by increasing activity in later years.

“However, a cumulative effect meant the sooner you started, the more influence you had on memory. We were not prescriptive about the type of physical activity in this study. It could be running, or it could be walking around the block.” How exercise acts to help the brain is an area of ongoing, intense study. Regular physical activity increases blood flow to the brain, stimulates growth of new neurones and their connections and is associated with larger brain volume. It reduces the risk of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, obesity and diabetes, which are associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia. “There is considerable dispute in scientific literature about the minimum amount of exercise required to protect the brain against age-related effects and dementia,” says Professor Perminder Sachdev, a scientia professor of neuropsychiatry, UNSW. “Our recommendation is to average at least 30 minutes a day – 60 minutes for children – including aerobic exercise such as walking, running or swimming on five occasions, and two sessions of resistance training. However, for those who have an inactive lifestyle, more may be needed, with some research indicating more than five hours a week.”

Social interaction

When it comes to brain health, loneliness is bad for you, and regularly engaging in social activity is associated with reduced risk of cognitive decline and dementia.

“Social engagement is cognitively stimulating and may contribute to building brain reserve,” explains McCabe. “Brain reserve is the degree to which a person can function, despite damage of the brain. It is known that individuals with a lot of brain reserve generally cope better with advancing dementia. Social engagement has also been found to have benefits for other health factors related to cognitive functioning such as cardiovascular conditions and depression.”

Professor Sachdev says, “The significance of social connectedness in relation to healthy brains is greatly underestimated. After tracking more than 1000 older adults for 12 years and controlling for a range of factors, a one-point increase in social activities was associated with a 47 per cent lower rate of overall cognitive decline. Those who were very frequently socially active enjoyed as much as 70 per cent reduction in risk of cognitive decline compared to those who were infrequently socially active.” Complex mental activity

Those who continue learning new things and challenging their brains are less likely to experience cognitive decline and dementia.

Almost one in five cases of cognitive impairment or dementia may be attributable to low levels of mental activity, more than any other risk factor. Research consistently finds a lower risk of developing dementia is associated with higher levels of education, more mentally demanding jobs and participating in intellectually stimulating activities. Working longer is associated with lower risk while earlier retirement has been associated with increased dementia risk. Cambridge University’s 2012 Cognitive Function & Ageing Study found people who were better educated, had mentally challenging jobs and were more socially engaged had a 40 per cent lower chance of developing dementia. Complex mental activities can include learning a new skill or language, volunteering or doing a course. Brain training programmes can also result in improved cognitive performance. McCabe explains it is important to vary mental activity. “Similar to muscle memory, our brains develop a memory for habits. Doing a sudoku or crossword every day is not going to be challenging once your brain learns the patterns and gets better at them.”

“There is an association between chronic stress and negative outcomes for brain ageing,” adds Michael Yassa, associate professor at Center for the Neurobiology of Learning & Memory, University of California, Irvine. “We know persistently high levels of the stress hormone cortisol can have negative consequences for brain cells and for facets of cognition including attention, learning and memory. Stress puts the brain in a vulnerable state, which makes it difficult to successfully repair itself, clear aggregating pathologies (which are linked to dementia) and reduce inflammation. Reducing stress by eliminating stressors, or by developing better strategies for stress management improves outcomes.”

A number of smaller studies report on the benefits of relaxation techniques such as yoga and meditation on reducing risk of mild cognitive impairment.

The importance of sleep

“Sleep is also critical for maintaining brain health,” says Professor Yassa. “Sleep has a restorative role for numerous functions. But one of the most important roles appears to be reactivation of experiences such that they can become ‘consolidated’ in our memory system and become more resistant to loss. Numerous studies have shown that sleep has the ability to enhance retention of learned information. Sleep deprivation is associated with worse memory and increased forgetfulness, among a host of other cognitive problems.” Early studies implicate a link between sleep loss and brain plaques, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease and evidence suggests this connection may work in two ways: Alzheimer’s plaques could disrupt sleep, or lack of sleep could promote Alzheimer’s plaques. Regular exercise, bedtime routines and avoiding alcohol and caffeine close to bedtime are strategies that could help to improve sleep length and quality. It may seem that mid-life is a logical time to start thinking about the modifiable risk factors of brain ageing. However, evidence suggests it is never too early – or too late – to look after your brain. Some risk factors such as old age and genetics cannot be modified, but there is a lot that can be done, starting today.

Keep your brain fit by keeping these simple lifestyle habits.