When you look into the eyes of an ape you see an intelligent, self-aware animal looking back at you. Appraising you. We don’t just descend from apes: we are apes. Humans are part of the Great Ape family and our evolutionary brothers and sisters are Chimpanzees, Bonobos, Orangutans and Gorillas.

We recognize their emotions as similar to our own. They are strong but gentle. They are patently smart: they use tools and can copy behaviour by observing it in others. These similarities make it easy for humans to anthropomorphize Great Apes.

Great Apes are named for their large bodies. Notably, they also have larger brains than other primates. We share the majority of our genetic material with Great Apes. Like us, they make and use tools, work together and form social groups in which they share and help others, even laughing with one another. They have strong family groups and distinct cultures.

Great Apes have their own language of gestures, similar to sign language or body language. They can pick up language just like human children do: by watching, listening and trying it out for themselves. Great Apes experience emotions and desires.

Great Apes live in Africa and Asia and tend to live in jungles, mountainous areas and savannas. Apes have offspring much like humans: giving birth to one or two babies at a time after a gestation period of around nine months. They breastfeed their young and take care of them for many years. For some species it can take twelve to eighteen years for the offspring to fully develop into an adult.

Many ape species are endangered — due to human pressure on their natural environment, being killed for bushmeat, or captured in the wild in the name of the illegal ape trade. They are exploited in zoos, circuses and amusement parks, and bought as pets. Great Apes can live for a long time. Chimpanzees can live up to 50 years in the wild. Chimps warn their friends of danger and even wage war over territory and kill one another.

Social learning is common in chimps. They learn to make tools from one another. They will eat just about anything. For a long time, we assumed they were herbivores, but it turns out that Chimpanzees are omnivores, meaning they eat both meat and plants. They use sticks to extract termites from their nests and they eat the meat of monkeys, in particular the Red Colobus monkey.

Chimpanzees make a new nest for sleeping every day. In fact, their beds are less likely to harbour bacteria compared to human beds because of this daily rebuilding habit.

Orangutans are the world’s largest tree-dwelling animal. They have the most intense relationship between mother and young of any non-human mammal. For the first eight years of a young Orangutan’s life, its mother is its constant companion. Until another baby is born, mothers sleep in a nest with their offspring every night.

The main threat to the survival of wild Orangutan populations is the massive destruction of tropical rainforests in Borneo and Sumatra fuelled by the global demand for palm oil.

Gorillas live in complex social groups, display individual personalities, make and use tools, and show emotions like grief and compassion. They use a range of complex vocalizations to communicate information in different contexts and are even capable of learning basic human sign language.

Mountain Gorillas are an endangered species, living in just two forests in central Africa: Bwindi and Virunga. Since they do not survive in captivity, the only conservation effort possible for the species is nature-based tourism — tourists visit wild habituated Gorillas, ensuring the necessary capital to protect the habitat.

Despite the growing number of tourists visiting Mountain Gorillas and an increasing number of habituated groups, very little data has been collected on the potential impacts of tourism on the behaviour of the Gorillas.

Case study: Mountain Gorillas and tourism in Uganda

Raquel Costa, Primatologist

My work aims to examine how interactions with human tourists influence Mountain Gorilla behaviour in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda.

This information will help the local authorities to develop management plans for Gorilla tourism that focus on minimizing disturbance levels for the animals, helping refine tourist education regarding their own behaviour in front of Gorillas in order to promote the animals’ typical calm behaviour. This aims to reduce the potential risks of conflicts as well as building the visitors’ sense of responsibility to enhance sustainable tourism.

Why do you do what you do?

I always wanted to know what animals were thinking. During my college years, I was introduced to ethology and found in it a way to get inside the minds of animals. I became interested in Mountain Gorillas, but no zoo in the world houses this species.

Moreover, the wild population was declining so rapidly that the species was feared to become extinct by the end of the twentieth century. It did not. Instead, in the past decade, the Mountain Gorilla population has more than doubled!

One important driver for its recovery has been nature-based tourism. By bringing tourists (and capital) to visit Gorillas, we ensure the protection of their habitat and the generation of local employment. But how do Gorillas feel about our presence? Is it good or bad for them? We do know that wild animals react to people in different ways: approaching, avoiding, attacking and annoying.

But it is less clear if this entails any stress or social disturbance for the animals. Maintaining the animals’ welfare is not just the ethical thing to do, it is also a necessity to keep nature-based tourism sustainable and contribute to the conservation of healthy Mountain Gorillas for many years to come.

What do you think is the public appeal of your animal?

Movies like King Kong and Gorillas in the Mist have helped to create a mystical view of gorillas. They are one of the strongest animals alive — they could easily kill you — but they have a shy and gentle nature. There is an appeal to get to know them better.

Moreover, being one of our closest relatives, we see ourselves projected in them. For example, gorillas’ family units come together to protect their infants as their primary function, which is also one of our society’s core functions.

What have been your biggest lessons learnt?

I was touched by the mutual respect between wild animals and local people walking side by side in Bwindi. I do believe that this respect was one of the major factors allowing the peaceful coexistence between both and, ultimately, the prosperity of nature-based tourism in the region.

On the other hand, I have seen tourists’ complete lack of respect for the established safe distance rules to be kept from the animals (7-metre/23-feet minimal distance for their safety and ours …). The risks of close association with tourists — who could bring new pathogens for which the Gorillas have no immunity — are severe.

Examples of this direct threat to the Gorillas’ health were sadly verified in the past, with reported lethal cases of infectious human-origin respiratory disease outbreaks in Gorillas.

What are your ‘strategies of hope’ for conservation?

Any conservation action will only work if the local community is involved, to effectively implement conservation management plans. In Bwindi, the local governments have created the mechanisms to overcome damage to local fauna and flora by using Gorillas to attract enough capital to protect the park.

Nevertheless, continuous monitoring is necessary to ensure the Gorillas’ welfare and health while also promoting public education. A peaceful and respectful coexistence of all parties (Gorillas, local population and tourists) with shared benefits between wildlife and humans is possible.

What are your hopes for the future?

Each one of us has the potential to become a conservationist. Tragic images — forests being burned, animals succumbing to trash we throw into the oceans — enter our screens by the hour. However, when facing so many disasters, we need positive examples to inspire and motivate us.

Nature based tourism, while still being refined for Mountain Gorillas, has already proven to have positive outcomes for the Gorillas and local communities. We need to ensure a fair distribution of benefits for both animals and humans.

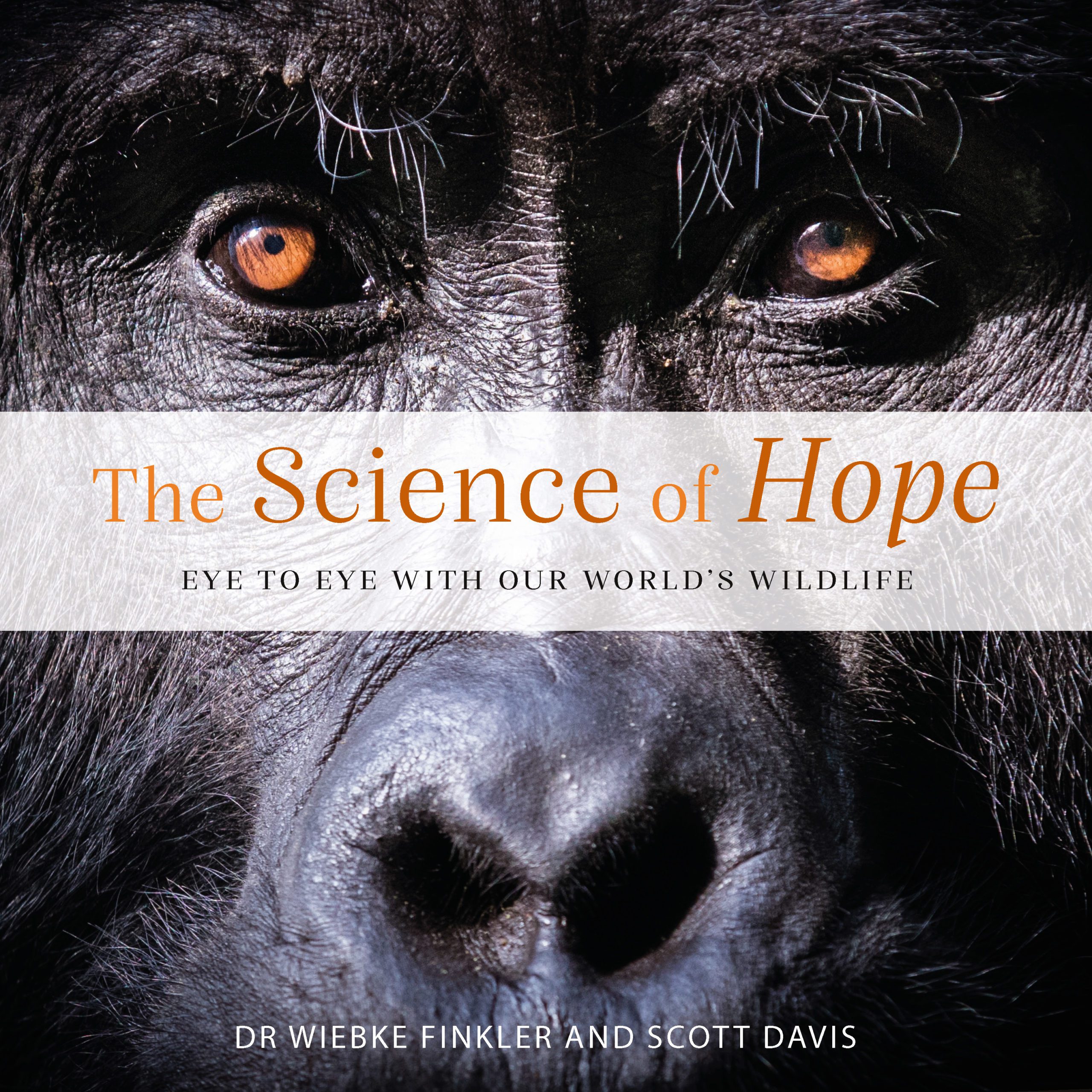

Written by a science communicator with a background in microbiology, Dr Wiebke Finkler, and featuring images from world-class photographer Scott Davis, The Science of Hope explores the science and psychology behind why certain animals capture the public’s imagination, while also highlighting positive conservation initiatives around the world.

The Science of Hope is available from exislepublishing.com and wherever inspiring books are sold. RRP$45.00 (NZD).