Currently in Victoria, there are around 12,000 children who cannot live safely at home. This number has increased by 21% over the past four years as more and more children are found to need out-of-home care in order to protect their safety and well-being.

Foster carers carry out a critical role in providing temporary, emergency, or long-term care for children who don’t have a safe place to call home. But in a time where the need for carers is more urgent than ever, we are facing a drastic shortage of carers – the lowest number in 20 years.

If you have the ability to become a foster carer, there has never been a more important time to do so. Not only does it support children when they need it most, but it’s an incredibly rewarding and fulfilling experience.

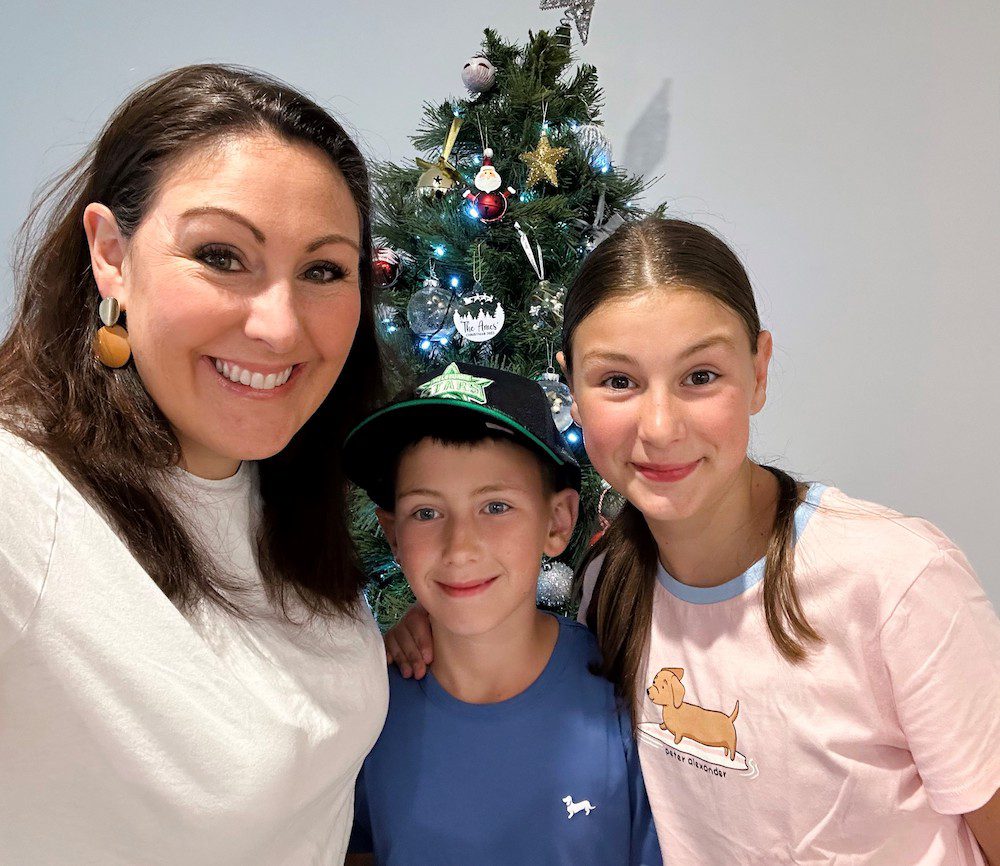

Read Holly’s story below to learn how becoming a foster carer has enriched the lives of her family.

Holly’s journey to becoming a foster carer

I was lucky to grow up in a safe and nurturing household with a mum who worked from home. On good days and bad days, she was always there for my siblings and myself, providing love and support no matter what we needed. It wasn’t until the age of nine, when my parents decided to become foster carers, that I realised many children didn’t have the safe, comfortable, and loving home life that I did.

Growing up with parents who are foster carers is undoubtedly a unique experience. Some nights you could be sitting watching TV and all of a sudden the doorbell would ring and another child would join you on the couch. I got used to introducing the neighbours to the new kids in our care as I played with them in the front yard or walked with them down the street.

I grew accustomed to seeing and hearing child protection coming through our house and learning the story that would come with each child. My parents took care of children of all ages, so some days I might be playing with someone my age, and other days I would be helping my mum fold cloth nappies and heat up bottles.

I saw the work it took to foster children, but I also saw how rewarding and fulfilling it was. So when I became a foster carer at around the age of 27, it felt right.

Now that I have children myself, I understand the motivation my parents had for becoming foster carers. By providing a loving, safe place for children to live – even if it’s just for a few days – I aim to show them a glimpse of what it feels like to belong to a good family network.

After becoming a mum, I also realised just how much it teaches children to grow up around foster children, just like I did. By becoming a foster carer, my own children have had to learn that the world doesn’t revolve around them. In a world where social media tells kids that their needs and wants are more important than anything else, I want mine to know that one of the best things they can do is contribute to their community and provide for others who need it.

They are also learning that others aren’t as fortunate as they are, just like I did all those years ago. They’re learning to share their mother and the time that they have with me. And they’re learning to see other children’s behaviours and how to navigate unfamiliar situations.

A big part of living in a home that takes care of foster children is learning to navigate relationships with people from all walks of life. Simple things like having to share toys has provided my kids with an opportunity to learn how to respond and react to people who haven’t been exposed to the same upbringing as them. I have no doubt that these skills are great for their own development and will make them kinder, more patient teenagers and adults.

Sadly, a majority of the children who come through Berry Street for foster care have experienced some form of domestic violence and trauma. The hardest part about caring for a child with trauma is that you can’t see it, so sometimes it can catch you off guard. There have been many times when I’ve looked at a little child and had the realisation that while they look content, they may be dealing with so much hurt and confusion inside their head. Berry Street provides incredible support to help carers navigate caring for traumatised children, and it’s a learning curve to witness how this trauma can manifest.

I experienced this first-hand when I was making dinner one night with a five-year-old boy in my care. At that point, everything was going well and he had adjusted to our family life quite easily. When dinner was ready, I went down the hall and yelled up the stairs to my two kids: “Dinner’s ready!” before turning around and noticing that this little one had shot down to the ground with his hands over his ears and started rocking back and forth.

I quickly realised that by yelling out to my kids – despite it not being done in anger – he had been reminded of the domestic violence he’d been exposed to in the past. I was eventually able to calm him and reassure him we wouldn’t yell again, ensuring he felt safe in our house for as long as he was there. Of course, I had to have a conversation with my kids about not yelling and how it can make others feel – a valuable learning experience about how we can make simple changes to help the children in our care feel safe.

This is just one example of how my family and I have had to work towards creating a very calm and stable household for the children in our care. We know that kids do better when there’s predictability – when they know what time they need to get in the car, when they know what they’re having for breakfast, and when they know you’ll read them that story at night.

If they’re not having to guess what might come next, that’s one less thing for their little minds to worry about. So often with trauma, children’s brains are always in a fight, flight, or freeze mode. If we can reduce some of the things they worry about, then we’re going to get a better outcome.

Routine and stability help to make them feel safe. Ultimately, however, it’s going to take time. This is the best thing you can give foster children to win their trust and help them feel safe. Remember that when they have been moved from house to house, they’re not going to trust easily. If you can provide them with consistent blocks of time and follow through with your promises – something as simple as reading a story when you’ve promised to – you’ll see positive results.

You don’t need to commit to becoming a full-time foster carer in order to make a difference. Some carers just offer weekends, weekdays, or emergency care. I’m a full-time single mother of two, so I’m busy within my children’s community, but I choose to make time for it because it’s a passion of mine.

With foster care, there’s a misconception that the child is dropped off and then you’re on your own, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. We know it takes a village to raise these children, especially when it comes to providing care that makes them feel safe, nurtured and loved – the way every child deserves to feel.

If you choose to foster, you will have a huge care team around you who will help you support the children in your care and make a difference in their lives. And, in my experience, they will make a difference in yours too.

We are in desperate need of foster carers right now. If you are interested in becoming a foster carer please visit the Berry Street website.