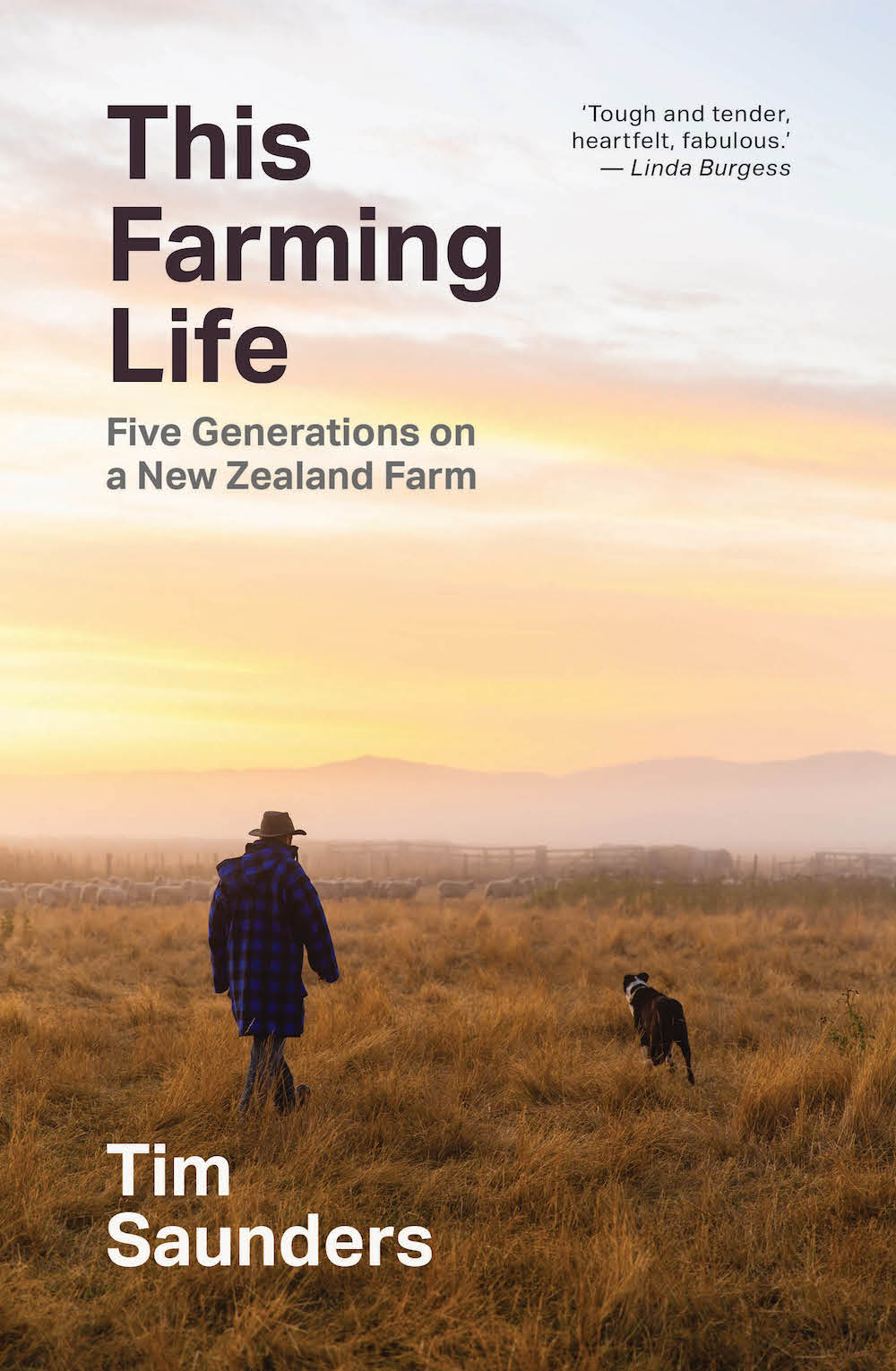

Saunders’ family has farmed the same piece of land for five generations – and now he has detailed his own experience as a farmer through a powerful and poignant memoir.

Having incorporated writing into his busy schedule as he worked his sheep and beef farm, Saunders takes us on a journey through the seasons.

In this honest portrayal of rural life, Saunders tells of his connection to the land, why he loves farming, how he’s also conflicted by it and what it is that keeps him tethered to that place.

And of course, having won our Short Story competition in 2018 with his piece ‘Walk to Work’, the author has the MiNDFOOD tick of approval.

Read an extract from Saunders’ book This Farming Life below.

This Farming Life

The moon made a rare appearance through the clouds and stretched my shadow across the woolshed yards, the silent night broken only by a sheep coughing under the macrocarpas and a steer braying ferociously in the darkness. Do sheep ever howl at the moon? This is the kind of stupid thought that strays into a tired mind.

It was 11 p.m., and it was my turn to feed the lambs. The lights in the woolshed flickered as a startled possum ran up the rafters, scuttling and scratching its claws on the mataī timber. My eyes got used to the dim light, as chilled air scrambled down my back. I started to measure out milk powder, added it to hot water from the tap in an old plastic jug that had been around forever. The markings had worn off, and I guessed the correct level.

Six lambs under the lamp needed feeding. The first clamped its tiny jaws around the rubber teat, guzzled the warm milk. The next needed a bit of coaxing. He pushed the teat out with his red tongue.

‘Come on, you’ve got to drink something.’

I held him between my legs, felt his body heat seep through my jeans, held the bottle in his mouth until he started to suck.

I cradled another lamb in my arms while feeding him because he was still too weak to stand. When I placed him back under the lamp there was yellow shit smeared across my jacket.

‘Gee, thanks.’

The old woolshed creaked and groaned in the night. The spirits of mataī trees haunted the walls around me. They always feel somehow closer when I’m alone in the shed at night.

There are ghosts scattered across the farm, their shapes cluttered haphazardly amongst the sheep. Sometimes I hear them high and lonely on the wind, or feel them guiding my hands. It is like watching somebody else’s hands straining the wires on a new fence or pushing the handpiece through the thick wool on a ewe’s back as the fleece curls to the floor.

I guess you could call it a collective ancestral knowledge, an ingrained instinct, a connection with the seasons. If I listen carefully, I can hear the empty echo of voices, that tiny space that exists between words but still carries meaning.

I observe myself making a myriad of decisions without thinking. When it is time to shift the sheep to a new paddock, when the crop should go in the ground, what crops to plant and what the weather will be like when harvest time rolls around. And I’ve learned to never second guess myself. Never think too deeply. Just trust that voice on the wind.

It can be partly passed off as intuitive. I often subconsciously look for signs—cabbage trees thick with flowers will mean a dry summer; the air and birds go supernaturally quiet just before an earthquake.

But I also like to think it is the ghosts of those who have trod these extant places before.

Even so, the thought of ghosts watching every move I make sure puts the pressure on. After this many generations on the farm, I don’t want to be the one who makes a cock-up, who brings it all down around our ears. Ghosts can be a burden in that respect. A spectral pain in the arse.

But I’m learning to trust them.

Dad actually saw a ghost once. Or at least heard one. He tells the story every year at lambing time, and we act as if we have never heard it. The fact is, we like hearing it. Our own little private scary story.

My grandfather died just three months after I was born. Smack in the middle of lambing, with a southerly storm tearing chasms in the sky and a shed full of bedraggled orphan lambs that needed feeding.

It was Dad’s turn to do the late feed, and he wasn’t happy. He was tired from long days and a new baby that woke him up every hour during the night. His coat had leaked as he sloshed his way to the woolshed, sending icy water cascading down his neck. Water had crept into his torch, causing it to short circuit. Only half of the lightbulbs in the shed were working, shadows scuttled across the floor into dark corners. The wind whipped unidentified heavy objects against the great wooden walls, an eerie dissonance in the darkness.

‘He sure chose a crook time to die,’ whispered Dad as he tried to get one of the sick lambs to feed from a bottle, its body unresponsive on his lap.

That’s when Dad heard the door squeak open and slam shut. Probably the wind, he thought. He had been meaning to oil the hinges for a while.

‘Who dat?’ he called. He was crouched down behind the large lambing crates and couldn’t see the door.

No one answered.

And that’s when he heard the footsteps. Not just any footsteps, but ones that were familiar. He had heard them thousands of times before. Two feet, then the hollow knock of a walking stick. One, two, knock. One, two, knock.

Grandad’s steps. ‘As clear as the nose on my face,’ said Dad.

The steps made their way across the wide mataī floor, and stopped just the other side of the lambing crates.

Dad froze. He reckons everything went quiet—the sheep, the lambs, even the storm stopped its deafening barrage against the roof.

He stayed there for ages. Not daring to move. Hardly breathing. Then the storm started to bash the sides of the night again, and Dad realised the sick lamb he was holding had finished the bottle and was looking a lot better.

The shed was empty when Dad finally looked around the side of the lambing crates.

‘What did you do then?’ I always asked.

‘What do you bloody think I did? I did my job and finished feeding the lambs. That’s what the old bugger would want me to do.’

Like I said, ghosts sure know how to put the pressure on.

Extracted from This Farming Life by Tim Saunders, published by Allen & Unwin, RRP $36.99