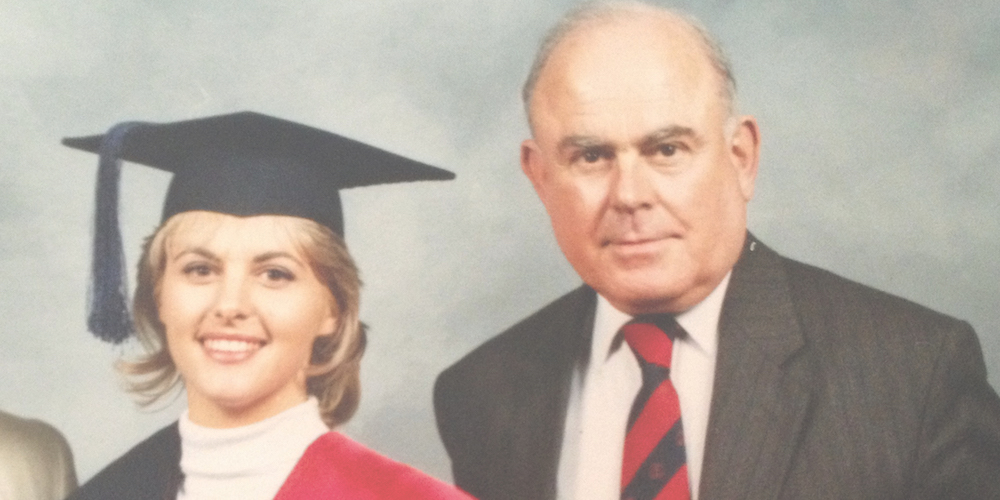

What to most of us is just a sensational headline, Margaret Ambrose lived through first-hand. She shares her all-too-real story of horror and loss with MiNDFOOD.

Whenever a murder is committed, the media’s money-shot is always a picture of the family. The victim’s mother, their husband, their kids – the public is hungry to stare into the face of someone who is experiencing the unimaginable. It satisfies our curiosity, our desire to know how it feels without having to actually go through the ordeal ourselves. Thankfully, catching a glimpse of those who have lost a loved one to murder is as close as most people will get to experiencing it.

Not me.

My father was murdered in 2005 and I can tell you exactly what it’s like.

If having a parent murdered isn’t sensational enough, my father was axe murdered. And if that sounds unreal, imagine what it must have sounded like hearing it from the mouth of a policeman.

Dad lived on a small farm in western Victoria, where he had moved when he retired from his career in accounting. He had thrown himself into community life and was well-respected in the area, providing financial advice to his neighbours and at the same time blitzing the awards for best pickles and jams in the local fairs.

Dad’s downfall began when he befriended a young junkie “rent boy”, who decided to blackmail Dad by taking his address book and threatening to call his family and friends and tell them that Dad paid junkie rent boys like himself for sex. Dad paid thousands to this man before deciding enough was enough and stopping. That was when the junkie decided to pick up an axe and end my father’s life.

the truth about murder

So what’s it really like to lose a loved one to murder?

The first thing you notice is that suddenly you have a lot of people in your life who were never there before and who you would never know or mix with normally. Junkies. Rent boys. Our lives were suddenly entwined and there was nothing we could do about it.

Then there were the friends and neighbours of my father, who we had never even heard of before, who spoke about my family to the media. Some even provided photos. They probably meant well, but when they talked about us to the press they put my family’s shock and grief – and yes, scandal – on the front page of the newspapers.

At the same time that the police were knocking on my door, they were also knocking on the doors of my brother and sister. I immediately phoned my sister, who said that the police had been sitting with her until another family member called.

There’s a well-oiled machine that handles the victims of crime. The police who broke the news to us were our local police. Their job was to talk to us before we saw it on the news.

When the homicide detectives came over that afternoon to explain things in more detail, they brought with them someone from the Victims of Crime Support Group, who brought with her information about all the services, such as counselling, available to us, as well as the forms to apply for Victims of Crime compensation.

Of course, this was just as well, because the shock and trauma of losing a loved one to murder leaves little room for thinking about anything else, but it is a sad reminder of the number of victims who have come before.

Life goes on

After the media circus has left town and life as you know it starts to resume, one change you notice is that you are scared. I wasn’t frightened that the junkie was going to hurt me or anyone else – he was in custody – but I was frightened of practically everything else.

What gets most people through life is denial of how random and dangerous it can be. We happily get into cars, even though we know the road toll, because we think, “Oh it won’t happen to me”; we enter into relationships even though we know that hearts get broken every day. But when the worst thing that could possibly happen does happen, you lose that ability to exist within denial. Don’t tell me the worst thing won’t happen – it already has.

When a relative is murdered, the world becomes a very scary place. You are made violently aware that at any moment your life can be tragically and irreversibly altered, even though you haven’t done a thing.

At the committal hearing of the man accused of raping and murdering ABC employee Jill Meagher, her husband stood on the steps of the court thanking people for all their support on what would have to be the worst day of his life.

When I heard this I felt physically ill, because I knew it wasn’t going to be the worst day of his life – things were going to get worse.

In the days and weeks after a loved one is murdered, shock protects you by numbing your body and mind to pain to some degree. You are surrounded by people who love you and want to protect you. And really, your life probably hasn’t changed all that much, in a sense of the day-to-day.

But at some stage life moves on. You go back to work, your friends go back to their lives, and although the people who love you are still thinking about you and caring for you, the murder no longer occupies all their thoughts. But it does for you, and dealing with the realities of the murder of a loved one while everyone around you gets on with their lives adds a layer of loneliness to the pain you are experiencing.

Far-reaching effects

Not long after Dad’s murder, I had breakfast with a male friend and we were talking about what had happened, when he started crying. Sobbing. Not caring about what other diners were thinking. I also later learned that some of my workmates had sought counselling.

Everyone is traumatised by murder. My friends, my colleagues, my relatives, they were all thinking: if this could happen to Margie, could it happen to me?

Eight years down the track and people are still being hurt by the actions of the murderer who took my father’s life. There are Dad’s kids, including me of course, and his friends. But there is a new generation of victims – his grandchildren.

I frequently think of Dad when I am playing with my toddler and infant, and think how he would have loved being a grandfather, and how my girls will never know that special relationship between granddaughter and granddad. The murderer robbed them of that.

The man who murdered my father was given 18 years in prison, which is pretty much the maximum he could have received, given that “life” is 25 years and time was required by law to be taken off because of his age and because he cooperated with police by pleading guilty.

So intellectually, I know there has been justice – but in my heart I don’t feel there will really ever be justice.

I’m not one of these eye-for-an-eye people who want to see murderers and other evil-doers strung up in the town centre. I don’t believe in capital punishment, and I do believe that there are always reasons why people commit crimes, and they are generally socio-economic.

Having said that, as long as my father’s murderer is waking up every morning and living and breathing, he will always have something that my dad has not. Life.

And I just have to live with it.