Photography by Russ Flatt

Renowned German photographer August Sander once said, “The portrait is your mirror. It’s you.” As a photographer who captured people from across all corners of his community, he may have been referring to a portrait’s ability to tell a story of society. But his words could be applied to Russ Flatt’s work in a more literal sense.

The Auckland artist, who cites Sander as a significant influence, creates works which reflect his personal life, staging intriguing scenes that reconstruct and interpret his own memories. Flatt (Ngāti Kahungunu) has recently been recognised with one of New Zealand’s highest honours in contemporary art, taking out the Paramount Award at the 2020 Wallace Art Awards wit a deeply personal photographic image.

‘Kōruru (knucklebones)’ depicts a red-headed boy and a young Māori woman sitting together on a dirt floor playing the titular game. The work was inspired by Flatt’s mother, whose family “whāngai-ed” a local boy with fair skin and flaming red hair, but the image also connects to his present family dynamic.

“During lockdown I was thinking a lot about my late mother, and I was feeling quite sad about the fact that she never got to meet my son,” Flatt explains. The artist and his husband, Alistair Wilkinson, have a son who came to them through the foster care system eight years ago. “I was remembering my mother and the stories that she would tell me, and then I made this connection that my son is, in essence, whāngai [a Māori customary practice of fostering].”

The presence of knucklebones in the piece invites the viewer to contemplate the value of play. “It was a game that taught you how to be with people, how to be in a group, how to share, how to win and how to lose. Just through play, it taught you a lot about existing in the world at a young age,” says Flatt.

The two subjects in the black-and-white work are positioned on a dirt floor in misty surrounds. Flatt explains that he wanted to create an in-between space that wasn’t recognisable; that was neither here nor there. “I’m still kind of learning what the piece is myself, which is really exciting,” he says.

For Flatt, the significance of the Wallace Award comes from being acknowledged by his peers in the artistic community. “It can be lonely, being an artist, unless you have a network of people that you engage with often,” he says. “I don’t really have that, and so the fact that the judges were all former Paramount winners, it actually gave me the strength to continue and it was nice to feel like I was doing something that was worthy.”

Flatt arrived on the New Zealand art scene relatively late in life, having worked in fashion photography in New York for 10 years. Tragedy brought him back to New Zealand and also triggered a transition to fine art photography. In 2007, Flatt’s father passed away, and while he was home for the funeral, his mother and sister were both diagnosed with terminal cancer. In the space of two years, Flatt lost all three family members.

“From that trauma, I would have these visions and nightmares and would often wake up screaming,” explains Flatt. “They were recurring, these things I would see, and so I decided to make a series about it. It was a way for me to process that trauma and grief.”

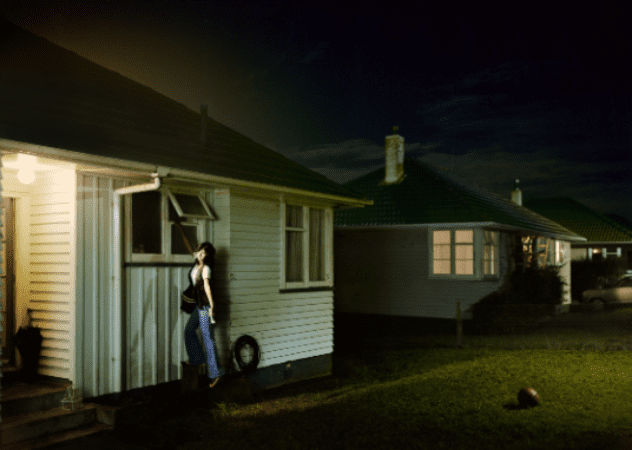

The result was 2010’sPaperPlanes, a collection of domestic scenes each telling a story about self and suburbia. The series also facilitated Flatt’ssegue into a fine art career, with the photographer using the works to gain acceptance into a postgraduate course at Elam School of Fine Arts. “That’s where it all began, when I started taking pictures that were for me and not for other people, or other people’s products,” he says.

Since then, Flatt has continued to produce thought-provoking works that both depict and enable him to process his memories of childhood and beyond. When Flatt embarks on a new project, it “overtakes everything”. “I spend every spare second thinking about what it is I want to say. I find with memory, a lot of what you remember is the hard stuff, the stuff that really traumatised you or makes you feel sad. So I fixate on those moments and make work about them.”

Flatt finds the subjective nature of memory also makes it a fun space to play in, and likes the idea of recreating moments that he can’t completely recall, instead “reconstructing them in a way that I hope makes people think”. A by-product of this examination of memory is an exploration of identity, and how it is formed and perceived.

“I didn’t really know what it was that I was making when I created that first series in 2010,” says Flatt. “It wasn’t until I went into the master’s programme at Elam that I was able to contextualise what it was that I was doing. There, I was given the freedom and platform to explore those areas that interested me, and it has just evolved.”

Growing up in suburban Auckland, Flatt says art didn’t play a significant role in his upbringing. But early in his career he began taking a fine art approach to his fashion photography, having been particularly influenced by the work of the aforementioned Sander. “He photographed people within his community who came from all walks of life and from different working backgrounds, and I was really interested in the stillness of those.”

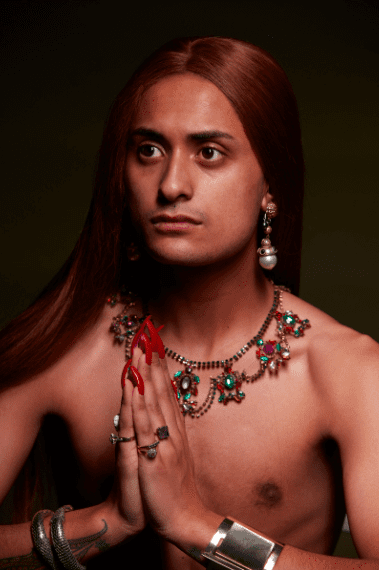

Sander’s ability to reveal and analyse character is echoed in Flatt’s work. Admirers of Flatt’s photography will recognise a cast of recurring characters, most notably a young man, Aniwa Whaiapu, who has featured in Flatt’s work since he was eight years old. “I really like the concept of people shifting and changing; it’s fascinating to me that this young man can embody so many different things,” says Flatt of Whaiapu. “And he’s so into it, he’s very engaged with the process and for that I’ll be forever grateful.”

Flatt was recently working towards a group show opening in February at Te Tuhi, a contemporary art space in Auckland’s Pakuranga. Titled A Very Different World, the exhibition curated by Ngahiraka Mason responds to the events of the past year and was positioned as having a “focus on wellbeing”, while promising to provide a “much-needed glimmer of hope for the future”.

Flatt notes that since creating ‘Kōruru’, he’s felt compelled to create further works dealing with more of what he calls “difficult subject matter that stimulates important conversations”.

Emboldened by his Wallace Art Awards win to explore these more challenging issues, Flatt says the recognition was valuable proof that people were reading his work in the way that he intended. “That’s all you can ever hope for as an artist, that people engage with the work and get something out of it.”

Russ Flatt is represented by Tim Melville Gallery, 4 Winchester Street, Auckland | timmelville.com