Waiting to meet Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, I’m introduced to an entourage of protection agents, photographers, sponsors and finally his private secretary, who signals a swift change of timetable and whisks me into the room 15 minutes earlier than scheduled. These sharp-suited Tibetans and their local counterparts run a tight ship, reminding me I’m about to meet one of the world’s most iconic figures.

While visiting Australia and New Zealand, giving public talks in most major cities and a number of Buddhist teachings to his followers at their request, the spiritual leader of Tibet blesses, entertains and educates his audiences. His favourite subject is secular ethics and is the topic of his recent book, Beyond Religion: Ethics for a Whole World. He describes this code of practice, based on valuing others, as being the simplest route to self-satisfaction.

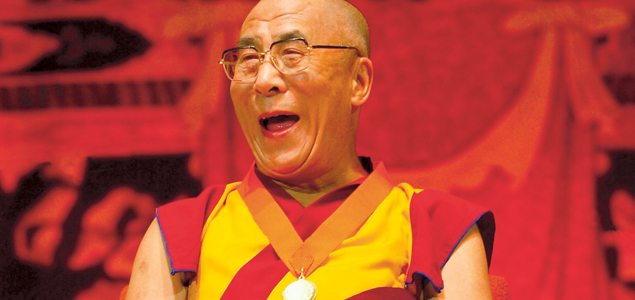

Despite receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989 and more than 150 awards and honorary doctorates, the Dalai Lama, who can draw crowds of up to 100,000, professes himself to be just an ordinary monk. As I step into his small lounge, I wonder if I will be received by a humble Tibetan or a formidable thinker and spiritual leader. To his followers around the globe, he is believed to be a manifestation of Avalokiteshvara or Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva of Compassion and patron saint of Tibet, provoking expressive adulation wherever he goes. My apprehension is dissolved when he gives me an expectant smile, a gentle handshake and a simple “Hello”.

Wise words

The Dalai Lama seems very much at ease welcoming a stranger into his lounge. As I wonder if a sip of water is available, my host calls to an aide: “Order juice! Order juice!” A tall glass appears in front of me and it seems this simple monk can read minds, confirmation perhaps of his otherworldliness. Once he is satisfied I am happy with my drink, and is composed in his armchair looking much younger than his 78 years, the interview begins. I hope to find out how a tradition that is 2500 years old can be relevant today, and how it can be adapted to our high tech, competitive society, where Eastern practices are offered as recreational distractions and spiritual iconography is appropriated by advertisers and the entertainment industry with little regard for its deeper meaning and sacredness.

I suggest that in the West there is a generally held belief that spiritual practice will diminish our personal power or blunt our ability to cope in a global community of dwindling resources. He accepts that working hard to overcome poverty is a motivating factor in all our lives, driving us to succeed, but believes it is the emphasis on external signs of success at the expense of our inner lives that creates problems. “It is very true that material poverty is a source of unhappiness and a source of frustration. So people naturally work hard to overcome that. The existing education system is also oriented towards material value, so then the whole of society develops into a new kind of culture, a materialistic culture, but it has no ability to provide us with peace of mind.”

How can spirituality exist alongside secular values based on individual freedom? “Spirituality is not something separate from ordinary human experience, not something higher.” He brings the notion of spirituality back to the simple equation of internal emotional peace being the foundation of harmony for society in general and explains how this sense of trust is nurtured in infancy. “We grow by our mother’s milk. So in order to understand mind and emotions, we must try to understand this early stage of emotional development in life: we need to pay more attention to affection. When you are born, your mother provides immense affection, enough to generate the determination to save her youngster’s life if it’s under threat.”

This is the core message of his secular ethics, a system of values that doesn’t rely on prescriptive religious guidance, but instead on a common language of human emotion derived from our earliest experiences and born of our basic need for affection.

Throughout our conversation I am reminded of his family origins and the conventional source of his wisdom, despite over 60 years of monastic training, studying Buddhist philosophy, science and medicine, and many years spent memorising sacred Indian texts. The Dalai Lama expresses great fondness and affection for his own mother and explains how he first learned to develop compassion for strangers and enemies from her, long before he fully embodied the practice of altruism enshrined in Buddhist scripture.

His Holiness stresses the need for scientific validation of his worldview and animatedly describes the studies that demonstrate how the brain is shaped by an infant’s tactile knowledge of its mother’s body and how this formative experience generates emotional stability in adulthood.

There is no trace of sentimentality in his admiration for a mother’s love. Logic is the foundation of his intellectual training – and with this to guide him, he connects ancient Buddhist philosophy to the modern scientific mind and regards this as the key to fully comprehending our humanity.

“We have to rely on the biological factor of our origins; the more warm-heartedness we can generate, the happier our family will be, and by extension, the whole of society will be happier. So a society that recognises the importance of inner values, and not merely the external signs of success, will be much better off.”

The message he wishes the world to understand is that our desire for a meaningful and contented life is possible without relying on a power separate from ourselves. Ordinary human experience contains the seed of our own divinity.

Finding the Dalai Lama

Unlike many other religious leaders the Dalai Lama is found, not chosen. Each successive Dalai Lama is believed to be a reincarnation of the last, meaning that each of the previous Dalai Lamas of Tibet is a reincarnation of the first, Gedun Drub, believed to have been born in 1391AD. Buddhists believe the Dalai Lama has the power to choose his reincarnated body.

It took four years to find the current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso. The search for a new leader is the responsibility of the High Lamas of the Gelpuga tradition and the Tibetan Government.

The High Lamas use various ‘‘clues’’ to help in their search,

from watching the direction the smoke takes when cremating the previous Dalai Lama to waiting for visions or dreams during meditation at Lhamo La-Tso – Tibet’s central holy lake. Legend tells of the female guardian spirit of the lake who promised the first Dalai Lama to protect the reincarnation lineage.

Once the clues lead to a boy, a series of secret criteria are used to ensure he is the reborn Dalai Lama. One exercise in addition to the rigorous process is presenting the boy with various items to see if he selects those that belonged to the previous Dalai Lama.

The reborn and his family are then taken to Lhasa where the boy studies Buddhist scriptures and relearns spiritual knowledge from his previous lives in preparation for the religious leadership.

While the search is usually limited to Tibet, the current Dalai Lama has warned there may be a chance that he will not be reborn and if he is, it will ‘‘not be in a country under Chinese rule’’.