Often, the solutions for saving the planet are found in looking forward —in developing new technologies and building modern solutions. But there’s also an argument to be made in rediscovering old ways and reimagining them with a new lens.

It’s this way of thinking that first inspired architectural engineer Fatma Abdelaal to pursue a career in the green building space. A civil engineering PhD student at the University of Canterbury, Abdelaal’s work focuses on sustainable building design, using a holistic approach to improve the built environment and reduce its environmental impacts.

This interest, she says, first came about at a young age, when admiring the architecture in her home city of Cairo. “I used to enjoy visiting historic buildings in Old Cairo and I used to wonder why it feels pleasant and comfortable inside these hundreds of years old buildings, regardless of the hot climate outside,” she recalls.

“Later on, I learned that these buildings succeeded in creating optimal indoor environments through implementing traditional green design concepts that minimised the impact of harsh natural environment conditions and utilised the benefits of local materials, natural ventilation, and natural energy sources.”

Recently chosen as one of the 26 researchers in the Commonwealth Futures Climate Research Cohort, who presented on a range of issues related to climate and the environment at the UN Climate Change Conference in November, Abdelaal is looking into green building rating systems and ways to improve homes and buildings for the health of people and the planet.

The genesis of her research topic links back to her startling experience when moving from Cairo to New Zealand in the winter of 2018. “I lived in a cold, damp and unhealthy home and was told that it is the common case for the majority of Christchurch houses. So, I decided to choose a research topic that can change that situation.”

In 2017, construction and operation of buildings accounted for 39 per cent of global carbon emissions, according to the 2018 Global Status Report. In an effort to meet the Paris Agreement of limiting global warming to below 2°C, the World Green Building Council (WGBC), which has more than 70 local councils around the world, has set an ambitious target for all buildings to be net zero carbon in operation by 2050.

“The environmental impacts of a building are determined by several factors including design, materials, construction, operation and demolition,” says Abdelaal. However, she adds, the majority of this impact can be attributed to the operation phase, such as the energy used to heat and cool a building day-to-day.

A ‘green’ building, as defined by the WGBC, is a building that “in its design, construction or operation, reduces or eliminates negative impacts, and can create positive impacts, on our climate and natural environment”.

These positive impacts include preserving precious natural resources like water and improving the health and wellbeing of the people who live, work and interact in these buildings. Smart metering systems, more efficient appliances and intelligent sensors illustrate different ways to address this impact, explains Abdelaal, and when it comes to new buildings, it starts with a “considered and environmentally conscious” design approach.

“The important thing is to start integrating sustainability at the early design stages,” she says. Scientists, researchers and companies are already pushing the envelope in sustainable design, construction and materials.

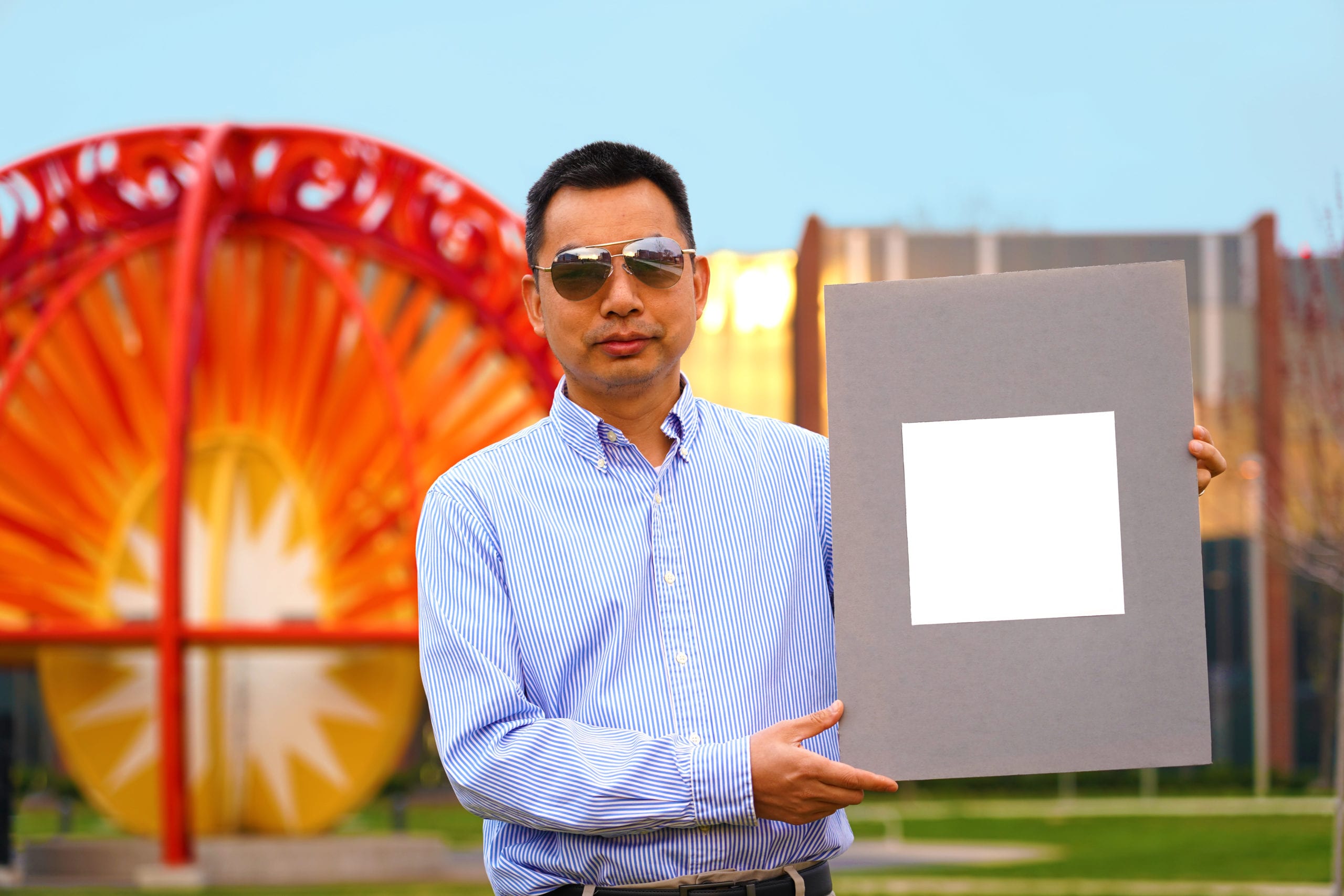

In April 2021, engineers from Purdue University revealed they had created the whitest paint in the world, able to reflect 98 per cent of sunlight and send infrared heat back into space, therefore creating a ‘cooling’ effect on buildings. The new tech takes advantage of centuries-old methods of using white paint to keep buildings cool, and could reduce or eliminate the need for air conditioning.

Other scientists have turned to bioceramics, material traditionally used in medical and dental implants, as an eco-friendly building material.

“[it is] a construction material that is energy-efficient, highly resilient to natural disasters including earthquakes and floods, and capable of absorbing carbon dioxide,” says Abdelaal.

California start-up Geoship is already making use of this technology, building carbon-zero, dome-shaped homes that could last more than 500 years. And with the potential for the bioceramic material to absorb carbon dioxide, buildings like these could in fact benefit the planet.

The progress is promising, but Abdelaal says there is much work to be done to meet the ambitious targets laid out by the Paris Agreement and WGBC. “Considering that around 1 per cent of new buildings worldwide are constructed to be zero carbon, it is a real challenge to the building industry that every building on the planet must be net zero carbon by 2050. But luckily, the design techniques and technologies for sustainable buildings are available, so this target is achievable.

“It is just requiring a genuine willingness to adopt them.”