An exhibition at London’s Royal Academy seeks to deepen our understanding of the post-Impressionist master Vincent Van Gogh by displaying not only his paintings and drawings, but many of his letters.

The Dutch painter wrote hundreds of letters during a productive career as an artist, most of them to his brother Theo who was an art dealer who supported him.

“The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and his Letters”, from Jan. 23-April 18, follows a 15-year research project into Van Gogh’s correspondence by the Van Gogh Museum and the Huygens Institute of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

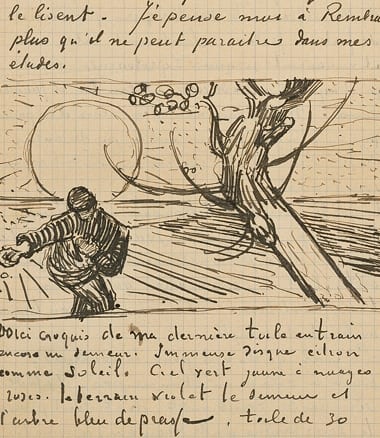

On display at what is predicted to be a major blockbuster exhibition are over 35 original letters, rarely displayed in public due to their fragility but which provide context for many of the 65 or so paintings hanging alongside them. The letters which contain the mundane — as in his description of a particular kind of pencil — and the poetic — as when he describes the waters of the Mediterranean as “like a mackerel” and “always changing” — challenge the notion of Van Gogh as an erratic and tortured genius.

“The popular view of him is that he was this kind of crazy, unreflective artist who just painted very quickly and very spontaneously,” said curator Ann Dumas.

“He did paint very quickly. But a great deal of thought and preparation had gone into his work even before he put paint on canvas,” she told Reuters.

Although he cut off part of an ear, committed himself to an asylum and ended his own life aged 37, Van Gogh was engrossed in his art and prepared to work hard to master techniques of perspective, colour and painting the human form.

“Much as I love landscape, I love figures even more,” he wrote. “Still, it’s the hardest part.”

When his “The Potato Eaters” was heavily criticised, he redoubled his efforts to portray humans effectively with studies of women digging potatoes and charcoal drawings of farm hands at harvest time.

His letters also reveal his struggle with perspective, which he wrote seemed to him like “downright witchcraft or coincidence”. By dividing his canvas with wires pinned across it, he was able to draw and paint “at lightning speed”.

Even at the very end of his life his letters reveal a man apparently more preoccupied with his craft than his personal and mental demons.

Days before his death, he wrote to Theo: “(I am) applying myself to my canvases with all my attention.”

In the last 70 days of his life, according to the Royal Academy, the artist painted more than 70 canvases, many of them among his most assured works. And that was despite a fear that his art had not progressed as he would have wished.

The unfinished letter which Van Gogh had on his person at the time of his suicide in 1890 is also on display with a note scrawled in pencil by Theo that said “the letter he had on him on 27 July, that horrible day.”

British critics have praised the show, particularly for focusing on Van Gogh and his art rather than his mental illness, self-mutilation and violent death.

“The genius of this show is that the artist himself tells us in his own words to look again and see what is really there, not what our imaginations have added to it,” wrote the Daily Telegraph’s Richard Dorment.

Reuters