Apple remembers a small front room where he was ushered in to see paintings of a candlestick telephone and Campbell’s Soup cans, one with a painted can-opener attached to the top. He in turn showed Warhol an image of the repeated photograph of the British ticket collector he had appropriated and adjusted with the addition of a red chinagraph pencil check mark.95

This was before Warhol took up silk-screening or found a New York gallery that would take his work; 96 when he still sold directly from his home to artists, collectors and curators who visited, having heard about his work on a grapevine that operated by word of mouth through talent scouts like Karp and John Weber.

In addition to seeking out artists, Apple got to know the dealers and their galleries, visiting Richard Bellamy’s Green Gallery, Martha Jackson, Sidney Janis, Stable Gallery, Betty Parsons, Allan Stone, Kornblee, Pace and, importantly, Leo Castelli, run by the eponymous dapper Italian who had opened his space at 4 East 77th Street in 1957, and had staked his reputation on Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, who broke with abstract expressionism and provided a vital bridge to pop. 97 The galleries were all clustered either on the Upper East Side around 77th Street, or in Midtown, especially on 57th Street.

The ones Apple frequented were the pick of the crop of those devoted to contemporary art, modelling the kind of clean, spare spaces that would become the norm for the presentation of new art. Here, each gallerist put together a stable of artists based on their particular taste and outlook, and ran a well-managed programme of regular exhibitions, which were advertised in the local media.

Gravitating together in favoured locales, these galleries formed a scene where the art world could congregate in the weekend ritual of exhibition openings; they were few enough to emerge as powerful brokers of what was considered important. 98

On his return to London in September he moved in temporarily with Richard Smith in the Bath Street warehouse he lived in and which he used as a studio, in Clerkenwell in London’s East End. Smith was a slightly older artist, an RCA graduate who had recently spent twenty-one months in New York on a Harkness Fellowship.

Since his return in 1961 he was producing large-scale shaped canvases based on abstractions of consumer products (such as cigarette packets) that registered his exposure to the eye-popping panoramas of America’s urban environments, with their billboards, neon signs, drive-in cinemas, skyscrapers and burgeoning retail outlets. His studio became a social hub for the art scene. 99

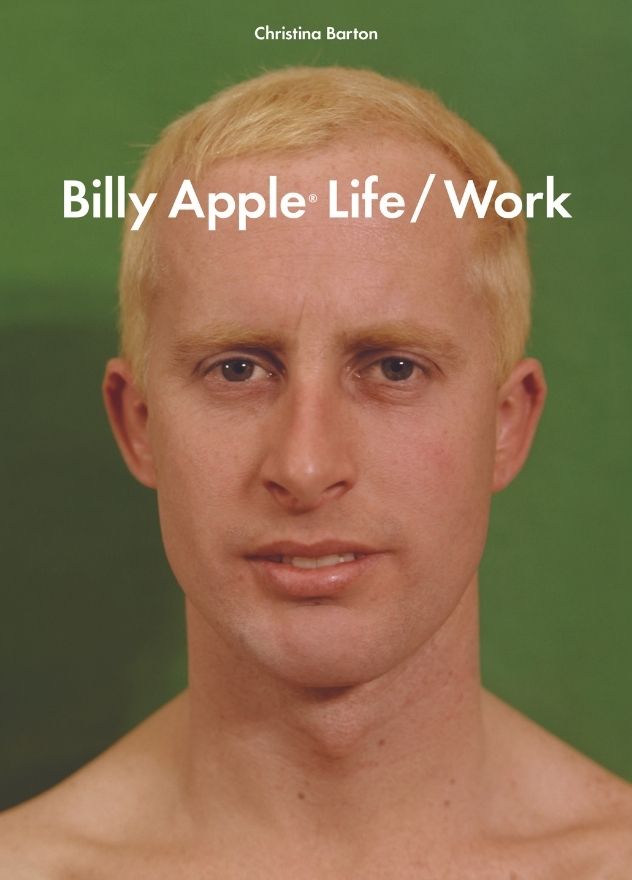

It was here, on the afternoon of 22 November 1962, that Apple and Smith effected the physical transformation that accompanied his decision to change his name from Barrie Bates to Billy Apple, and thus reinvent himself. To launch his new identity, Apple bleached his hair and eyebrows and Smith documented his transformation in a series of colour slides.

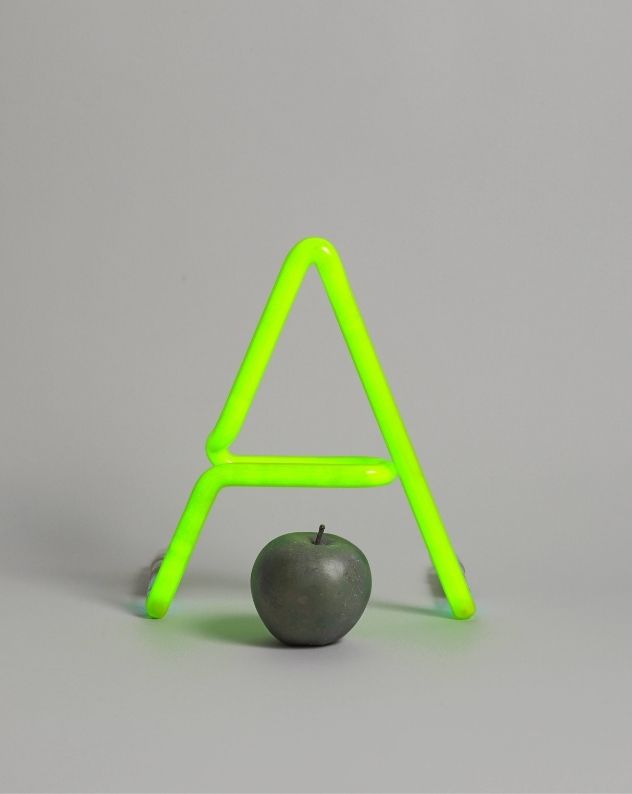

Together they had settled on the name in a brainstorming session that had them playing with various options. ‘Billy Apple’ stuck because it was simple and catchy and sounded like a fresh product rather than a person. 100 It drew on the wholesome properties of the fruit, as well as its multiple linguistic and narrative associations. For example, ‘apple’ is the word we associate with the letter ‘A’ when learning the alphabet; and apples play common roles in origin stories, such as those of Adam and Eve and Johnny Appleseed.

Though undertaken privately with no other witnesses, Apple always understood this as an artistic appropriation of the workings of the marketplace, where restyling a product was commonplace. He spoke of this as Barrie Bates’s ‘last work’, a move that would require him to live as his own art work from that day forward.

Something of the nature of this conundrum is embodied in the photograph Apple now treats as the principal document of this moment: Billy Apple Bleaching with Lady Clairol Instant Creme Whip, November 1962 (1962/2002). This is a black-and-white print made from the original 35 mm colour slide taken by Smith showing the artist with his newly bleached hair looking at himself in a mirror, his blond pate illuminated by the almost divine glow of a partially visible light bulb.

Here we witness the transformation of Bates into Apple as a curiously humdrum Immaculate Conception. We see the subject split, literally, by the act of representation. The clue to the photo’s uncanny effect is the mirror into which Apple so piercingly stares. Because of the angle of the shot, from the viewer’s perspective there is no reflection, so Apple is presented as a miraculous original, an intangible presence within the image.

As well as a record of the event that would shape Apple’s career from that day forth, this photograph is a telling analogue for what happened to the artistic subject in the era of mass consumption; it makes ‘Billy Apple’ an emblem of his times.

Apple’s use of bleach to dye his hair to restyle himself recalls his and Hockney’s first encounter with the American television commercial they saw in 1961. Hockney recorded his own transformation into a blond in The Arrival, the first plate of A Rake’s Progress (1961—63), the suite of etchings he produced to document his trip; and it became a recognisable feature of his artistic persona, an attribute, like his distinctive glasses and tongue-in-cheek waistcoats, that identified him as a new breed of artist.

In contrast, Apple’s change of hair colour was an integral component of a more radical gesture, whereby the artist completely walked away from his old self in the interests of a total and incontrovertible rebranding. From that day he taught himself to not respond when people called him by his previous name.

He stopped writing home and cut himself off from his old friends, especially fellow antipodeans like the New Zealand artist Jeanne Bensemann and her Australian sculptor husband, Neil Stocker. 101

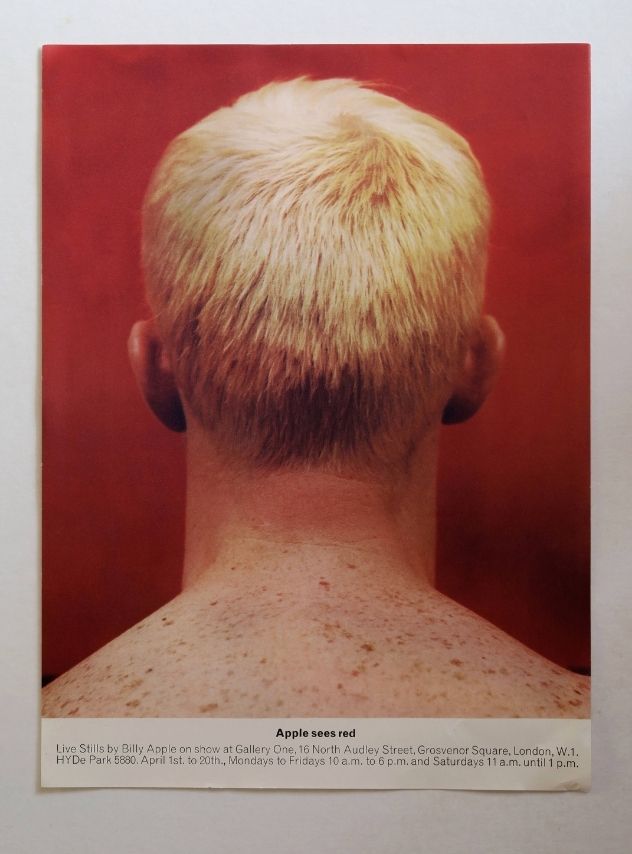

As the final step in his reinvention, just before Christmas 1962, Apple had himself photographed by Robert Freeman (who was then working on the new Sunday Times Magazine and, the following summer, would begin a long association with The Beatles, producing art work for five of their album covers). 102 Freeman shot Apple in close-up from front and back, focusing alternately on his facial features and his bleached and closely cropped hair; portraying him by turns as pin-up and product.

***

95 This work would later become Relation of Aesthetic Choice to Life Activity (Function of the Subject), with the red check mark replaced with neon.

96 An exception, before Castelli invited Warhol to join his gallery in 1964, was a solo show at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery in November 1962.

97 Apple recalls being introduced to Castelli by Jasper Johns (whom he had met through Robert Indiana). Conversation with the artist, March 2009.

98 Apple’s firsthand contact paid off. In December 1962, several of the bronzes he had produced at the RCA were included in Nuts and Bolts!, a group show at Allan Stone’s gallery at 18 East 82nd Street (11—29 December 1962). Apple was included as Barry [sic] Bates, though by the time the show was launched, he had become Billy Apple. Other artists in the exhibition were Steve Antonakos, Bruce Breland, George Deem, Irwin Fleminger, Wayne Nowack, Gerd Stern and Helen Stoller.

99 It was here that Ken Russell shot the wild party with which Pop Goes the Easel — his experimental documentary about British pop art — ended. Screened on BBC television in 1962, this followed four young artists — Pauline Boty, Peter Blake, Derek Boshier and Peter Phillips (all from the RCA) — as they worked and played in London’s streets, studios, shops and bars, effectively capturing them as freewheeling contemporary flâneurs.

100 Apples were one of New Zealand’s primary exports to the UK at this time and to secure its hold in this market the New Zealand Apple & Pear Marketing Board made New Zealand’s first television commercial. This was a series of three short animations made by Goldberg Advertising and produced by Morrow Productions; with a catchy tune featuring the line ’Fresh up with an apple’, they showed a young man cheered up and made well by grabbing and eating an apple, or posing with one on his head that is speared by an arrow. This was screened on British television c. 1960. See https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/set/ item/40, accessed July 2019.

101 Conversations with the artist and Jeanne Macaskill, c. 2010.

102 A comparison between Freeman’s photographs of Apple and his first cover for The Beatles, With The Beatles (1963), is instructive. Both feature close-up head shots of their subjects that focus on their distinctive facial features. There is also a striking resemblance to Freeman’s back- view head shot of the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev taken on a visit to Moscow in late 1962 for a story that was published in the Sunday Times Magazine (Apple has kept the page from the magazine, which is stored in the artist’s archive).