When asked which of the five senses they would give up, most people opt for smell. When we compare it to other senses, smell just doesn’t seem as helpful, right? Ann-Sophie Barwich would disagree.

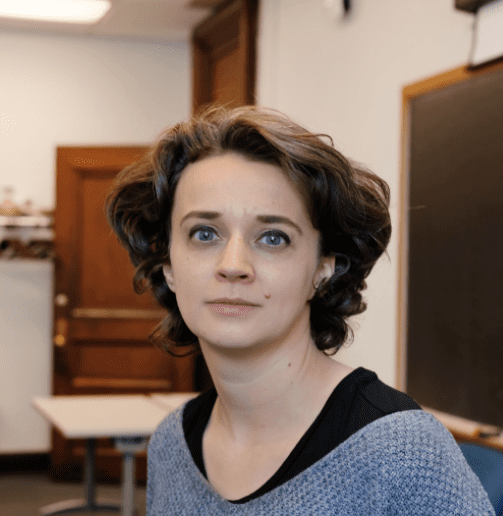

A cognitive scientist and philosopher, she is obsessed with all things smell. A champion for this sensory underdog, she’s carved out an expertise in the area of olfaction (the sense of smell) as an assistant professor at Indiana University Bloomington. Her recently published book, Smellosophy: What the Nose Tells the Mind, seeks to highlight the important connection between smell and the brain.

“Smell has been called unsophisticated, brutish and in evolutionary decline, instinctive, subjective or merely ‘emotional but not cognitive’,” she says. “Nothing could be further from the truth.”With anosmia (smell loss)emerging as a common symptom of COVID-19, olfaction has recently experienced some time in the spotlight.

However, says Barwich, up until just a few decades ago, smell was mostly considered an “eccentric footnote” in the history of science. “It was neglected because it was extremely difficult to turn the ephemeral nature of smell into standardised laboratory settings and experimental frames. As Alexander Graham Bell once asked: ‘How do you measure a smell? How can you tell whether a smell is twice as strong as another?’”

In 1991, olfaction was propelled into mainstream science, when scientists Linda Buck and Richard Axel discovered the nose’s receptor family. What they found was a molecular goldmine – the gene family that encodes the odour receptors is the largest in most mammalian genomes.

Since then, scientists like Barwich have sought to explain the misunderstood aspects of olfaction. Take the idea of having a ‘bad sense of smell’, for example. “This is a very common misconception. When you test people’s abilities, they turn out to be fantastic smellers.”

In fact, humans can perceive some odorants in the ten to single parts per trillion.“ An example is TCA, a compound that causes the aroma of corked wine. Imagine I pour a teaspoon of TCA into last year’s entire wine production of Australia and New Zealand – that wine would smell of nothing but TCA to you! There is a big gap between people’s awareness of their senses and their real abilities.”

The humble nose is, in fact, incredibly sophisticated. Some 400 types of scent receptors livein the nose, which give humans the ability to detect at least one trillion different odours. One of the biggest misconceptions, Barwich explains, is just how much of a role smell plays when it comes to taste.

The tongue can identify the basic five tastes – sweet, salty, sour, bitter and umami – however, it’s the nose that gives food the many other dimensions of flavour. “You don’t have a strawberry or apple receptor in your tongue. It’s your nose that provides you with that.”

Although the nose has the ability to identify many different odour molecules, it’sthe brain that puts that smell into context and turns it into a mental image. During her research, Barwich wanted to demonstrate how the brain processes the smell sensations and how that process can be manipulated. She organised a workshop with master perfumer Christophe Laudamiel, in which participants were given a smelling strip with a molecule called sulfurol.

“It was hard to pin down what that smell was. Its melled organic, fatty, slightly sweet … He then showed an image of warm milk. And suddenly you thought: ‘Of course, warm milk!’ It was right there, in your mind. He then switched the image to ham. And, I kid you not, the milk was gone, and you smelled ham. It blew my mind!”

The point of the experiment, she notes, is not that smell is unpredictable or erratic, but that the same molecule can come from multiple sources.

Understanding how the brain interprets smells also offers a new way of thinking about how the brain works. “The visual system has tempted us to view the brain as a mirror of the world,” says Barwich. “But I think that the brain processes smell much more like a measurement instrument: what, how much, in what ratio and combination we encounter smelly molecules.”

From a philosophical perspective, Barwich says there’s plenty to explore around the unconscious side of smell and all the hidden ways it affects our everyday lives. “Smell links our feeling of connectedness with the world. Anosmics (people who have lost their sense of smell) often mention a strange feeling of disconnect from their material surroundings. You usually never know what you have until you’ve lost it. To understand how the mind works, we must look beyond the sensations we are consciously aware of.”

Since Buck and Axel’sbreakthrough in 1991, the science of olfaction has advanced incredibly quickly. Barwich says technology such as neuroimaging will continue to play a key role in making sense of scents. “Technology has allowed us to turn many longstanding observational prejudices upside down.”