Glass art is in global demand for its beauty, delicacy and technical flair; yet it is a craft that requires much dedication from its practitioners. We meet four Kiwis who not only have the skills and passion to create amazing glass works, but are also willing to share their personal experiences and their incredible art with the world.

Photography by Greta Van Der Star

Other Kiwi dads might have tinkered with cars in the garage or dabbled in a spot of home DIY from the shed – instead, Luke Jacomb’s dad pulled molten lumps of glass from a furnace in the backyard and blew them with his mouth into pieces of art.

John Croucher, now in his early seventies, is one of the pioneers of glassblowing in New Zealand, and in recent years has become internationally renowned for his advances in the chemistry of coloured glass.

Jacomb, 43, is a chip off the old glass block, known both locally and abroad as a major and multifaceted talent in glass art. But despite growing up in such an auspicious environment, Jacomb wasn’t always keen to follow in his father’s footsteps.

“My dad started working with glass around the time I was born, in 1977,” says Jacomb, “and he and a bunch of his crazy friends in Ponsonby were the pioneers of the glassblowing movement in New Zealand. Basically what happened is that they built this furnace in the backyard and dribbled glass all around the backyard at parties and then after that, they were like, ‘Oh dude, we’re going to be glassblowers’. And it actually worked out that they became glassblowers,” he says.

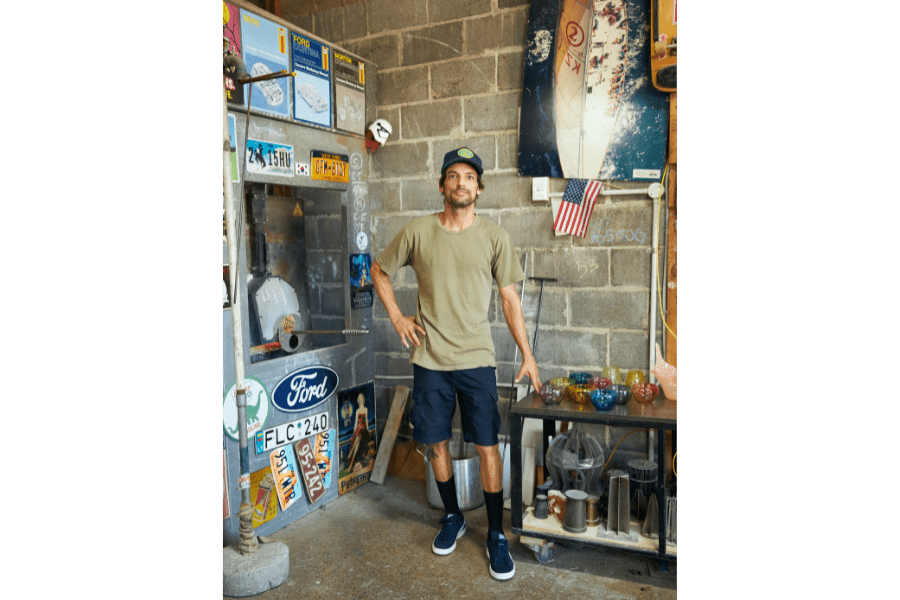

“I grew up around glass and I kinda thought that it sucked when I was a kid – I was more into skateboarding and hip-hop and goofing off with my friends – but I started working with glass in the early ’90s and I was kind of into it, it was a good way of making some pocket money,” Jacomb says. “Around ’93 or ’94 this guy called Callaghan moved over from Seattle, an American guy a few years older than me. I thought he was really cool, he was into skateboarding and all sorts of cool stuff, and he told me that glass was cool. And because I thought he was cool, then it was cool.

“So then I went and told other friends of mine, like Matt [Hall] and Simon [Lewis Wards] that lived in the neighbourhood – this is around the time that we were finishing school – so they thought it was cool, and we all went and worked for my dad. “After that we’ve all just really worked with glass, and each other, ever since.”

Jacomb describes glass art as “a very seductive thing”. “Once you start working with glass you realise, oh sh**, this is really, really hard, it’s like, harder than skateboarding hard! So I started taking it quite seriously when I realised it was difficult, and I’m very competitive.”

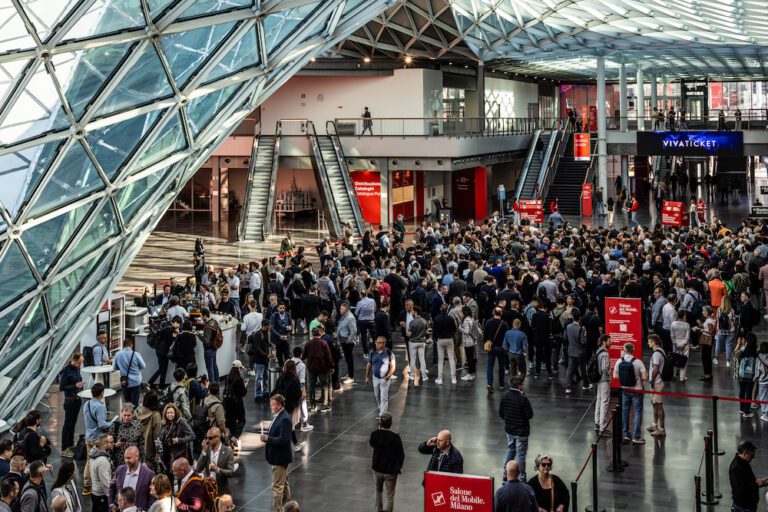

That competitive nature saw Jacomb make the move to the United States, spending “four or five years in New York and four or five years in Seattle”. “There’s a few places in America that are glass meccas, and I ended up at a couple of these meccas,” he says. “One of them was in New York, at the Corning Museum of Glass – they have this huge collection of glass and they have people that come and study from all over the world.”

There he got a job, skilling up on every kind of glassmaking process through history in order to demonstrate how pieces from the collection were made to an audience of museum guests numbering in their thousands each day. “Basically I was being paid by a museum to learn how to make hundreds of different objects and be very well versed in them, so it was an unbelievably rare opportunity,” he says. “I was really lucky, to get that job, because it was such an accelerant for my skills. I got training from glassmakers in Murano and other really fancy good American glassmakers. “I learned very quickly, and just being immersed in an institution like that, you just learn so much, there were libraries, and I got shown a lot of things behind the scenes that other people didn’t get to see.”

Returning to New Zealand, Jacomb set up his own studio, Lukeke, with partner Katherine Rutecki, and set about using his remarkable skill set and passion for glass not only to create amazing glass art but also to share his experience with other local makers. As well as teaching, mentoring and providing job opportunities and work experience in his Auckland studio, Jacomb has organised international expeditions to glassblowing hot spots such as Shanghai, Prague and Venice.

His latest major venture, The Crystal Research Institute, brings Jacomb full circle back to working with his dad. “He has got his own office there and all these fancy machines and ways of testing glass and that sort of stuff. “So we’re doing research on figuring out how to make different glasses that haven’t been made before, to add to that family of 70,000 varieties of glass in the world,” says Jacomb.

“Lots of other artists around the world would agree that he’s probably one of the best coloured-glass chemists that the world has ever seen; he’s extremely talented at coming up with formulas for making glass. “He built a very successful company [Gaffer Glass], which is now based in Portland, Oregon and they supply a lot of the world’s market with different glasses, but he’s not there, he’s trapped here with me in Auckland.

“I don’t really know what it’s going to be yet,” says Jacomb. “I just know there’s stuff that I need, that it’s going to be a place where we make stuff for ourselves. “There are lots of scientific and industrial glasses that have never been brought into the artistic world, so he’s like a conduit, to try to push these technologies into the art world.”

MATTHEW HALL

Matthew Hall was introduced to glassblowing thanks to his close friendship with Jacomb, which dates back to intermediate school. He first started working with glass when he was 18, when Jacomb organised a job for Hall at his father’s company Gaffer Glass.

Hall was the ‘bottom rung’ of the team rolling glass bars on an industrial scale. “It was hard work but such an amazing start when I look back at it,” he says. After working his way to the top of the bar-rolling team, Hall went on to be an assistant for Auckland-based artists John Penman and Peter Viesnik. Hall and Jacomb have worked together since the latter returned to New Zealand after working and training in the United States. “Luke is an amazing glassmaker and has an incredible breadth of knowledge to tap into,” Hall says.

Through working with Jacomb, Hall has had opportunities to gain his own experience from travels overseas. “I feel very lucky to have made the pilgrimages to Murano and the Czech Republic with Luke and the Lukeke team,” he says. “We visited museums and private collections, and during our time in Murano, we stayed on the island and studied goblet making with [renowned Italian glass blower] Davide Fuin.”

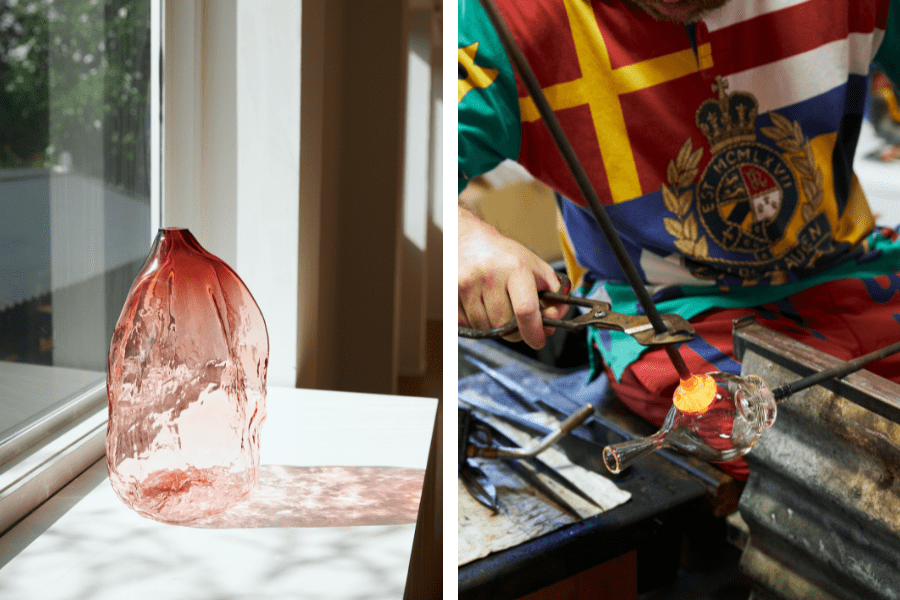

Back home, Hall is also proud to have worked with ‘lots of incredibly talented’ visiting international artists, such as Nickolaus Fruin, Dylan Martinez, Preston Singletary, Jerry Kung and Martin Janecký. For Hall, his love of working with glass is all to do with the process and appreciating the way in which the medium moves.

He uses classical glassblowing techniques to make fun, functional forms that use light and negative space to show the movement of the hot glass. “For me it’s the perfect mix of head, heart and hands; of science and art that ties me to centuries of rich tradition,” he says.

Hall is currently in the design stages of a new series inspired by textiles and fashion, and is in the process of building his own studio at home. Additionally, he is kept busy with keeping the galleries and stores that sell his work stocked up.

Hall’s ability to keep his cool, literally and figuratively, in the hot shop has served him well throughout the years. “You have to stay calm at all times, even when things are going wrong,” he says. “Lots of water and electrolytes.

KATE MITCHELL

While studying at Elam School of Fine Arts, Kate Mitchell reached out to Jacomb in the hope he could answer a few questions she had about glass. Jacomb not only answered her questions, but gave her a job with the team at Lukeke. She’s been working with Jacomb ever since.

Mitchell’s work is distinctive in the way she applies colour to her vessels. Her signature confetti tumblers are created by rolling fresh hot glass onto a palette of colourful pieces. The appeal of working with glass for Mitchell comes from the colours and textures that can be used and created with it, and also the effect light has when interacting with it.

“Coming from a background of painting, I often think of glass as the ultimate painting medium,” she says. “Clear glass is like my empty canvas, used to create the shape and form of my piece. Colour is my subject, which can be applied in endless different techniques. Light is the gloss that brings the final piece to life, illuminating the colours and form of my piece.”

As a woman in a male-dominated field, Mitchell says it’s both tough and rewarding to work as a female glassblower. “Glassblowing is mentally and physically challenging and is not for the faint- hearted,” she says. “It’s empowering to prove that women are as equally capable to work alongside men in this environment. I am also lucky to work alongside great male artists, such as Luke and Matt, who are very supportive and fun team members.”

Throughout her more than five years of working with glass, Mitchell has figured out how to cope with the physical challenges of glasscasting and blowing, where there’s no hiding from the intense heat. “I have decorated myself with small burns, sweat out gallons of liquid and have experienced many heartbreaking moments of work smashing against the concrete floor,” she reveals.

“I have slowly built up stamina that enables me to move through the heat, pick up broken pieces and carry on. Of course hydration is very important, and accepting that there will always be good days and bad days in the hot shop.”

This year Mitchell is set to turn her attention to lampworking, which involves using a torch to melt and shape glass with more detail and intricacy than in the hot shop. “I’m going to be using my lamptorch to make smaller glass components outside of the hot shop that I will later incorporate in my glass blown pieces,” she says. She is also planning on using the technique to make glass beads, with the hope of launching some jewellery later this year.

SIMON LEWIS WARDS

Simon Lewis Wards’ work has always been rooted in nostalgia. He is best known for his representations of iconic Kiwi lollies, calling to mind childhood trips to the dairy. “I make pieces that evoke feelings from my own childhood, and have found that they seem to resonate with others, too,” he says.

Counting Jacomb as one of his best friends since they met at school, Lewis Wards is another Gaffer Glass graduate. “Quite a few of our group of friends worked for John [Croucher] over the years,” he says. When Jacomb returned from the States, Lewis Wards helped him set up his glass studio in Newton.

“I became very interested in the casting process and made my first pieces which were glass power poles,” says Lewis Wards. “He introduced me to a few gallery owners who liked what I was making and within a year or so I had set up my own small studio, which I’ve since expanded out to a 300 square-metre studio in the Waitākere hills.”

While his work is recognisable for its ‘Kiwiana’ aesthetic, Lewis Wards has had significant experience abroad. Between 2015 and 2018 he lived in Paris, where he set up a small studio. “I didn’t have the same access to space and equipment so it gave me the opportunity to develop my skills in copper foiling, which is a stained glass technique,” says Lewis Wards.

During this time he also travelled to the Czech Republic, where he trained at one of the oldest glass-casting schools in the world and learned from master caster Petr Stacho. “It was like travelling back in time; it was the most amazing place I’ve ever visited.” Lewis Wards credits his work with glass for making him a much more patient human.

“All of the parts of the casting process take time, and if you try and rush it the glass is unforgiving. It just breaks,” he says. In addition to glass, he works with a range of ceramics and concrete and is looking to expand more of his work into other mediums.

Last year he released his first limited-edition run of screen prints, which was well received, and he has another run in the works. He worked on several larger-scale public pieces last year, including a suspended sculpture containing 400 glass jumbo jet planes.

“I enjoyed the challenge of these projects and have a few more concepts I’d love to realise,” he says. “I’ve just finalised plans for my first solo exhibition which will take place at Kina Gallery mid-April so will be fully focused on that for the next month or so.”