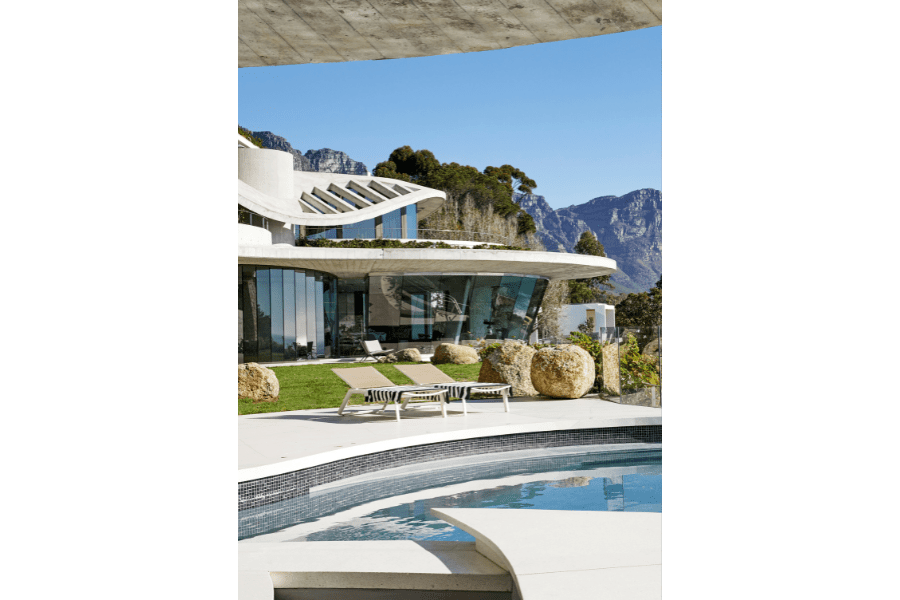

Inspired by the heady, futuristic aesthetic of ’60s and ’70s LA modernism, this home injects some of the era’s glamour and poolside party lifestyle.

High up on Cape Town’s gorgeous Nettleton Ridge, hugging the craggy mountainside and overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, is a vision that might make you think for a moment that you’d entered a parallel universe. You could be looking at Tony Stark’s Malibu mansion from the Iron Man franchise or a Bond villain’s lair, or even something out of The Jetsons.

And you wouldn’t be far off: this Clifton house, belonging to mining banker Lloyd Pengilly and designed with crucial input from his son Hanno, has its roots in the same US west coast architecture that inspired these filmic fantasies, particularly the work of John Lautner. Perhaps the most famous of Lautner’s designs is Palm Springs’ Elrod House, which is featured in James Bond’s Diamonds Are Forever. Another, the Sheats-Goldstein House, pops up in The Big Lebowski.

They’re LA party pads, rising organically from their rocky mountainsides, their interiors fusing with their vast views: part stone sculpture, part flying machine. This house has a similar sculptural presence, at once futuristic and primal. Its swooping curves and waving contours evoke the jet-set era: a time when airports and flights were glamorous and romantic, when space travel had captured the world’s imagination, and when cars spelled freedom.

Cape Town firm Peerutin Architects [now Peerutin Karol], who designed the architecture, worked closely with Silvio Rech and Lesley Carstens (SRLC), responsible for the interior architecture and design. “The result is a seamless continuation of the exterior expression to every detail of the interior,” says architect David Peerutin.

He explains that Lloyd and Hanno didn’t want just another “box-like structure that stood in opposition to its site”, so one of his main challenges was to design a large house – the 90-metre wide, 20-metre deep site is unique in Clifton – that wouldn’t impose on the landscape.

“We decided on a conceptual idea of a structure that mimicked this undulation in its forms and specifically the leading edges of each level. In our design there are some more direct translations of the iconic forms that characterise Lautner’s work, but these were adapted and integrated into a much broader expression of this architecture,” says David.

The house is split over four levels. The bottom two are clad in stone to mimic the mountainside. “As a direct and deliberate contrast to the solid base, the upper two levels, containing all the living [and] entertaining spaces, and the bedrooms are designed as a light, sculptural group of ‘free-forms’ that weave indoors and outdoors together,” says David. Silvio describes them as “concrete ribbons, dancing, twirling in the wind.”

From the street, you enter through the garage, and from there, through a copper-clad sliding door and a lobby. A spiral staircase leads to the next level, with a bar, entertainment area, indoor swimming pool and guest bedrooms. Up one more level there’s the main living area with a lounge, dining room and kitchen. “[The top level] is made up of two sweeping flying saucers and a bridge that links them,” explains Silvio.

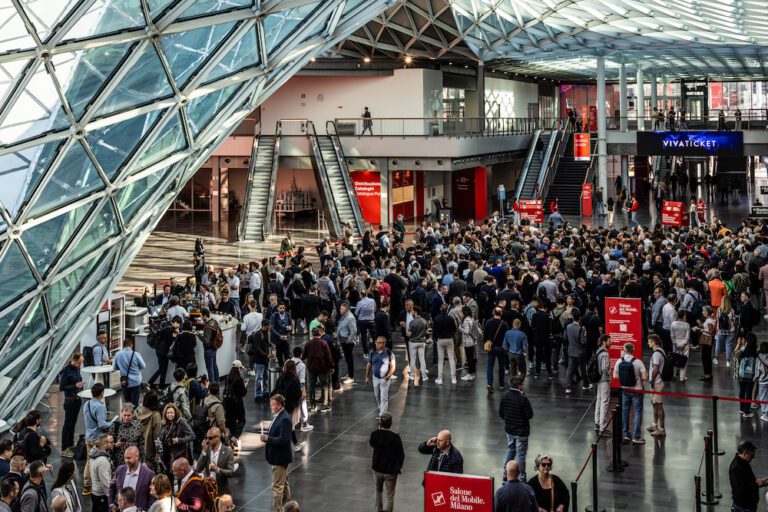

Across “a green lawn in the sky” is a circular concrete party pavilion with a swimming pool, spa and sunken bar. Silvio and Lesley immediately understood that the experience of the house had to be elevating and uplifting: “rising above the everyday chores of normal life”. “It has one of those timeless, endless, extended views that is just so magical,” Silvio enthuses. For a time, their studio was filled with LA photographer Slim Aarons’ images of poolside glamour.

There were thumbnails of every James Bond villain’s lair they could find pinned to the walls. In fact, watching vintage Bond films became mandatory for the studio’s team. Like the architecture itself, of course, their approach to the interior architecture wasn’t simply a matter of duplicating Lautner’s interiors – it was more a matter of translating and adapting it for a new place and time.

They restricted the material palette to just a few key materials: the raw concrete of the architectural shell, beautiful Palissandro Brasil wood panelling, and large sheets of granite that connect with the rocky materiality of the mountainside.

White terrazzo covers the floors. Although they sourced key furniture items, Silvio and Lesley also designed an array of bespoke furnishings and finishings for the house, including bar counters, sofas, bed units, desks and dining tables.

Some of the furniture that Silvio and Lesley sourced for the house is of the era – Platner tables and chairs with mustard upholstery, for example – while others are more contemporary iterations of the mid-century philosophy. Patricia Urquiola’s Husk armchairs, the Tom Dixon lights and even the bespoke curved sofa by SRLC all represent a contemporary take on mid-century modernist design.

Throughout, the house has an organic connection to its setting: high-tech but grounded. The main living area was designed to look like a patch of the beach below the house had “sprung up” and reconfigured itself as a plush living room.

Lush indoor planting pushes up between the volumes of the stairwell and sheets of water, such as the pond at the entrance, with that copper-clad wall behind it, represent something elemental at the heart of the house. The granite indoor swimming pool feels at once like a strange laboratory and an underground cave.

It’s the kind of house where a poolside party becomes something of an artwork. In fact, Silvio loves to quote Lautner on the subject: “To me, architecture is an art, naturally, and it isn’t architecture unless it’s alive. Alive is what art is.”

Photography by Greg Cox, words by Graham Wood