By the time Simon Shahin and his family left Damascus, Syria, it was all but uninhabitable. To leave the house was to toy with death. “Where I was living, not a day would go by without a mortar shell falling nearby or some shooting; it was just a war zone,” he says. “The terrorists were less than a kilometre from where I was living and, if I went out, there was a big chance I would be killed. It was dangerous just to go from your house to the supermarket. No one can describe that feeling – it was quite terrifying.”

It’s now five years into the civil war that has displaced almost half of its population – more than four million people have fled Syria and an additional 6.6 million have lost their homes. According to the United Nations, the fighting in Syria has so far killed at least 470,000 people, including more than 12,000 children.

Lucky few

Shahin and his family are some of the lucky few to escape and find a new land to call home. They arrived in Sydney last August after being granted refugee visas while still in Damascus.

“The time was frozen for us for the past four or five years,” Shahin says. “It was an intense atmosphere to live in, especially for my younger siblings. It was stressful for them, exhausting. We’ve lost a lot of people and seen people killed before our eyes. It was crazy. The memories are flashing back.”

Although he was in his fourth year of university, Shahin could no longer attend classes because of the war and, because he couldn’t get to his final exams in safety, couldn’t graduate. Surviving simply took priority.

When news came that the family’s application for asylum had been approved, Shahin says it was overwhelming. “We could breathe out,” he says.

Syria’s civil war began in 2011, when government forces responded violently to protests against President Bashar al-Assad’s regime. The military opened fire on demonstrators and reportedly tortured and killed numerous activists. Armed civilians formed rebel groups to respond in kind and the fighting has since escalated to a destructive and deadly war.

Of the millions who’ve lost their homes but remain in Syria, life is beyond difficult. According to Amnesty International, the government and armed groups such as Islamic State (IS) are restricting the delivery of aid to people in need, and medical supplies are so scarce that, even when they make it to hospital, the sick and injured are dying, sometimes of starvation.

Around 13.5 million people are in desperate need of humanitarian aid within Syria, and the number is growing as rebel groups clash with the army and pro-government forces.

Instead of taking decisive action to save lives, Amnesty International campaigns director Meg de Ronde says the global community is failing in its responsibility to protect the world’s most vulnerable people.

“The world is facing a humanitarian catastrophe of vast proportions. There are more women, men and children in desperate need of protection and a safe home than at any time since the second world war,” de Ronde says.

“We need to see a new, humane approach in the way the international community deals with this global refugee crisis; it requires a global response instead of what has so far been a piecemeal approach.”

Increased Quotas

Australia showed glimpses of global human rights leadership last year by announcing the resettlement of 12,000 Syrian refugees, says de Ronde, but both Australia and New Zealand must do more. “Glimpses are not enough. Australia must lift its refugee quota to at least 30,000 people in 2016 and end the regime of offshore detention,” she says.

In mid-June, New Zealand announced it would increase its annual refugee quota to 1000 in 2018. The current level of 750 people per year was set nearly 30 years ago.

“The fact that New Zealand is 94th in the world when it comes to refugee resettlement is embarrassing,” says de Ronde. Prior to the June announcement, the New Zealand government promised to welcome 750 refugees from Syria over the next three years. Of that number, 150 are within the annual quota and 600 places are via a special emergency

“The next step must be an annual increase in the quota to meet the growing need for resettlement places,” adds Grant Bayldon, Amnesty International’s executive director.

Conflict around the world

Syria may be where most refugees are currently coming from, but it is by no means the only country facing difficulties. Over the past year alone, conflict in Yemen has seen 1.1 million people displaced and half a million people have left their homes in South Sudan. Many people are also being forced to escape ongoing violence in Afghanistan and Iraq, abuses in Eritrea, and troubled nations elsewhere.

Before the crisis in Syria, most of the world’s refugees were fleeing Afghanistan – a situation that had held true for more than 30 years. According to the Refugee Council of Australia, about 2.6 million people from Afghanistan remain refugees.

Significant hardship

For those who make it to Australia, settling in takes time. “Refugees and people seeking asylum have often faced significant hardship that is difficult for many Australians to imagine,” says Violet Roumeliotis, CEO of Settlement Services International (SSI), one of the not-for-profit organisations providing valuable support to new Australians trying to adjust to new lives.

“Many refugees have experienced great hardship in their home countries and suffer from psychological trauma from torture, war and separation from family,” Roumeliotis says.

SSI works closely with STARTTS, a service for survivors of trauma and torture, to provide culturally appropriate psychological treatment to refugees needing to heal the scars of trauma, along with a range of initiatives designed to help them tap into their strengths and build social connections – starting from the minute they land at the airport.

A case manager connects each new arrival with housing and support services and arranges orientation sessions that introduce them to public transport, doctors, supermarkets and banking services. SSI’s Ignite Small Business Start-ups initiative makes the most of the entrepreneurial skills, knowledge and experience of refugees by supporting them as they navigate Australia’s business environment.

“Many Ignite participants have established their own businesses in their home countries, and helping them to tap into their strengths and start something new is a real boost, both emotionally and financially,” Roumeliotis says.

A challenge and a blessing Jana Matic looks back on her transition into a new life in Australia as both a challenge and a blessing – she lived through four years of war in former Yugoslavia before fleeing her home near Sarajevo and finally arriving in Australia as a refugee a year later.

“It was only two years after coming to Australia that I started to relax, to start experiencing life again,” says Matic. “I started to have panic attacks then and I think that was all a result of me starting to trust and relax and to admit what I had just been through – trauma from war, trauma from coming to a new country and trauma from losing my identity.”

She was 19 years old when she flew into Sydney and the only English she knew was, “Can I have a glass of water?” – a phrase she learnt on the plane. “The first three months after arriving, I found it really hard, I was going to go back,” Matic says. “Being such a social person and not being able to talk to anybody who I could relate to and who could relate to me – that was the hardest.”

She had also come from a culture where physical contact during conversation was normal. When people stepped back from her “touchy feely” style of communication, she took it as rejection. “There were a lot of social things I needed to learn and adjust to, to even talk to someone so that they felt comfortable with me. I adjusted, but it felt really cold to me.” Now 39 and a yoga teacher in the Blue Mountains near Sydney, Matic says it’s only this year that she has truly started to feel at home. “It’s taken 21 years to feel I have community and that I belong somewhere.”

Nazeh Diab and Mirvat Hassan with their children, Jinan, Ahmed and Maria (pictured above)

Country of origin: Syria Current home: Auckland, New Zealand

When shooting erupted outside their home in a southern suburb of Damascus, Syria, Nazeh Diab and Mirvat Hassan knew they had to help. They invited the injured inside and treated some of the wounded.

On the second day of fighting, they knew they had to leave. In the hope things would be better when they returned, they left for a month. When they tried to come home, however, the situation had worsened, with mortar shells being dropped nearby each night.

It was no longer safe for the children to go to school. To make matters worse, word had got out that Diab and Hassan had helped the injured; they were warned to leave immediately.

“You cannot stop and think, there is no time to think, you have to move,” Diab says. They spent an hour packing before walking through fighting to get on a bus headed out of town. They were lucky to survive – they were shot at on the bus and a sniper’s bullet went between Hassan and their son, Ahmed, before going out the other side of the bus.

Before the war, Hassan says life was good in Syria. Family and neighbours supported each other, healthcare and education were free, and people of all religions happily co-existed. “We had a perfect life,” she says.

When they left the country they loved, they also left behind their house, jobs and large extended family. The school where Hassan used to teach Arabic is now a centre for people whose homes have been destroyed. Now two or three families live in each classroom.

The family left Syria in 2012 and lived in Thailand until they could be resettled in Auckland in March 2015. None of the family had heard of New Zealand before they came.

When they found out where they were going, they scanned a map of Europe looking for New Zealand. “We thought it was in Switzerland,” says Hassan. The children had not been to school for four years when they arrived in the country, and daughters Maria and Jinan found it hard at first to make friends.

“I think we think: ‘Kids make friends easily.’ But this isn’t the case when there is a language barrier,” says Hassan. “The school put in a huge effort to help them adapt. Now they are much more comfortable.” All three children are now enjoying school, and some of Ahmed’s friends have even begun to learn some Arabic. Ahmed wants to be a biologist when he grows up, Maria wants to be an engineer and Jinan hopes to be a dancer.

Jana Matic

Jana Matic

Country of origin: Bosnia Current home: Blue Mountains, NSW

When the first grenades fell near her home at the start of the Bosnian War, Jana Matic and her brother would stay home from school and hide in the bomb shelter. “Soon it wasn’t a novelty any more and then we were going to school when grenades were falling. Life goes on,” she says.

“I think the hardest bit was not having enough food. My responsibility was keeping myself safe whereas the reality for Mum and Dad was different – it was feeding the children and providing for us.

“The third year in the war was the hardest,” Matic says. “It was the coldest winter.” Electricity was limited to two hours in the middle of the night and they would have to walk to the natural springs to get water for drinking and flushing the toilet.

Matic was 19 when she fled the apartment she shared with her family near Sarajevo in former Yugoslavia. She had lived through several years of the Bosnian War before her father and brother escaped and sent word for Matic and her mother to do the same.

They left everything behind but for a small bag each her mother had sewed the night before. Matic packed a few photos, a ring her grandmother had given her and one change of clothes.

The experience has taught her she can adapt to any situation. “I know if I lived through that I can live through anything. I only need the bare essentials. Just having a roof above your head, food and people that appreciate your views is all you need.”

Matic, now 39, runs a Kundalini yoga studio (infinitepulseyoga.com.au) from her home in the Blue Mountains and is married with two children.

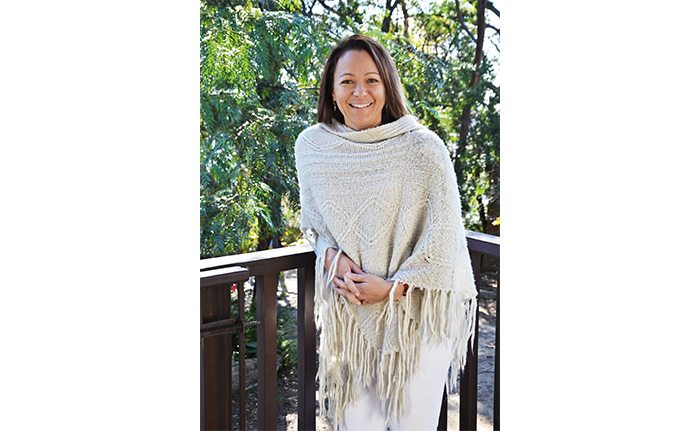

Nohara Odicho

Nohara Odicho

Country of origin: Syria Current home: Sydney

Before the war, Nohara Odicho was a third-year student studying agriculture and engineering. She was a member of a church youth group and loved going camping with friends.

“I had a normal life like any young person. Then the war came and everything changed. It was hard to leave the house. I miss my old life, and being with my family and friends. It was an easy life.”

She and her father came to Sydney in June last year, after the war had made it too dangerous. “Everything was really bad and we heard the shooting and bombing all around us. We had to go.”

Odicho tries to focus on the positive, but the trauma has stayed with her. “When it was Chinese New Year, I was sleeping and heard the fireworks and then woke up and remembered all the shooting – I thought the same thing was happening here.”

Although the 23-year-old is embracing the challenging of learning a new language and starting again with her studies, her 64-year-old father is finding it hard to settle. “He finds it difficult. My brothers are not here and he wants all the family to be together.

“We didn’t know where to go at first – Sydney is a big city. Learning how to find things and places to go took a while. We had great support from SSI and our case manager, but it’s the small things that are hard at first. It takes time. With time, everything will be easier.”

Her brothers are in Iraq waiting for their visas to come through. Odicho is studying community services. “I’d like to be a case manager to help settle new refugees – to help them find their way and find a new life here.”

Gracy Tlumang

Gracy Tlumang

Country of origin: Myanmar Current home: Dunedin, New Zealand

Gracy Tlumang was 12 when she left the little bamboo house she shared with her grandmother and siblings in Myanmar for the safety of Malaysia, where her mother had fled four years before.

The Chin people are a minority Christian group of Myanmar. They face severe discrimination and attacks because of their faith.

“For a whole night we went in a tiny fishing boat to Thailand with 50 people. We had to crouch and lie down, covered with smelly fishing nets so we wouldn’t be seen,” she recalls. “I was so scared.”

From there, she hid in the jungle by day and travelled to Malaysia by night, by turns on foot and crammed into a small car with 10 other people. Because she was slight, Tlumang – now 20 – rode in the boot. “I hate small, dark spaces now so much!” she says.

After a two-week journey, Tlumang arrived in Malaysia and ran straight into her mother’s arms. “We cried a lot but they were happy tears.”

Tlumang and her mother shared a room with five others in Malaysia for four years before being granted asylum in New Zealand. “We cooked, ate, and slept there. Sometimes landlords made us move – refugees in Malaysia get a lot of trouble.”

The biggest surprise about her new home in Nelson was that she had a bedroom to herself and a bed to sleep in. “I had never had a fridge or a washing machine before – we didn’t know how to use them,” Tlumang says. “Volunteers helped us with everything.”

Her four siblings now live in Nelson, too, and Tlumang is studying health science at the University of Otago. “I want to be a pharmacist. I’m so lucky that I am here.”

Simon Shahin

Simon Shahin

Country of origin: Syria Current home: Sydney

“I am in the beginning of this journey,” says Simon Shahin, who left his home in war-ravaged Damascus to come to Australia last August. He had only ever travelled to neighbouring Middle Eastern countries before landing in Sydney, but is quickly learning the ropes.

Shahin was very overwhelmed when he arrived. “Everything was different – the people, the places, and the customs – but Australians are very friendly and hospitable. I’m not just saying that to give a compliment: I’m making many friends and each one is teaching me something new. Settlement Services International (SSI) has helped me meet many people.”

Now 23, Shahin is the oldest child in the family. His younger siblings are in school, his mother is learning English and his father is studying to pass the admissions test for dentistry – his profession in Syria. “He is working hard at it; his English is very good.”

His grandparents are still back in Syria, along with a lot of friends and other relatives. “I worry about them; they tell me it’s getting worse and worse.” Shahin had completed three years of university study before coming here. He has had to start again in his quest to become a renewable energy engineer, but is unfailingly positive.

“I think it was Steve Jobs who said that those who are crazy enough to think that they can change the world are actually the ones who do so. “I have lots of plans and ideas, and I am looking forward to the day I can contribute to this wonderful country that welcomed me with a warm heart.”